Date: Jun 26, 2019

The “enfoque de género” (gender-based focus) within the Colombian peace accords is currently a global example for inclusive peace, particularly for the inclusion of women in peace processes. The overall language of the accords has also successfully included victims of diverse backgrounds, including sexual and gender minorities. The reality of implementation on the ground, however, is grim.

There have been major setbacks to the implementation of the gender stipulations of the accords; as of June 2018, only a mere 4 percent of the gender stipulations were implemented. What is more, there has been a backlash to the inclusion of sexual and gender minority groups in the 2016 peace accords, especially evident when observing the rejection of the first version of the accords in the October 2nd plebiscite.

The first version of the peace accords was signed in September 2016 and then put to a popular referendum. Voters narrowly rejected the peace accords, in substantial part because of efforts by some evangelical pastors and conservative members of the Colombian Congress to portray the accords as containing an “ideología de género” (gender ideology). This rejection led to the second version of the accords, signed and passed in November 2016. The sentiment behind the rejection of the first version is what is most concerning.

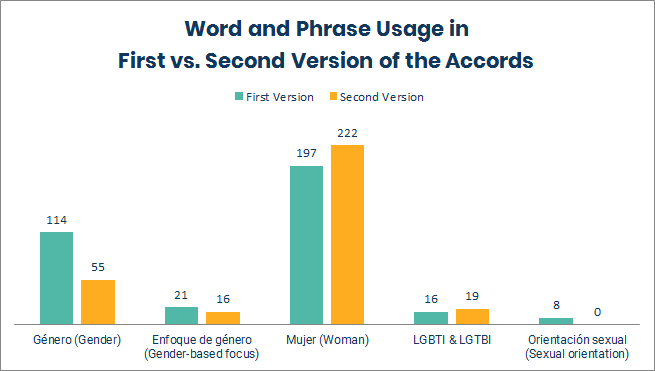

When observing what changed in the language between the first and second versions of the accords, although LGBTQ+ rights continue to be mentioned throughout the accords, the wording on sexual orientation was completely eliminated from the final version of the accords, making it clear that the attack was directed primarily at the LGBTQ+ population in Colombia.

What triggered the eruption against the “gender-based focus” language of the first version of the accords? The spark that ignited the controversy came right before the first version of the accords were signed, when the fear over the term “gender ideology” became inflated—from an issue unrelated to the accords themselves.

In August 2016, the Ministry of Education published an informational pamphlet, titled “Ambientes escolares libres de discriminación” (“Discrimination-free schools”), to be used in Colombian primary schools in order to promote more inclusive education and encourage gender and sexual equality in the school environment.

The publication of the pamphlet was followed by public outcry, led by some Evangelical leaders over the fear that such education would promote a so-called “gender ideology” which, according to these opponents, threatens traditional family values and encourages homosexuality. The outrage and protests spilled over into the campaign against the “gender ideology” in the peace accords and those opposed to the peace accords also used the specter of “gender ideology” as a way of undermining support for the Yes vote.

Though the phrase “gender ideology” is not mentioned in the peace accords, Cedecol, an association of evangelical churches in Colombia argued that the “gender-based focus” reflected the “gender ideology,” stating:

“We conclude and ratify that “Gender Ideology” does exist in the Havana Accords between the Government and the FARC, because: Despite that the “Gender-based Focus” of the accords begins with the protection and promotion of women’s rights, the transversal language makes evident an additional conceptual level that includes and employs terms such as: “gender diversity, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender perspective…” Therefore, the term “Gender-based Focus,” [and its] sphere of application promotes a new anthropology of the being, that ignores…and denies the differences and reciprocity between man and woman; even though the word “ideology” does not appear in the text, it is reflected through the terms mentioned above.”

Adamant opposition particularly by certain pastors, the government’s highly conservative current ambassador to the OAS, Alejandro Ordóñez, and conservative members of Congress played a major role in the rejection of the first version of the accords and forced the Colombian government to make amendments that erased many of the mentions and rights of the LGBTQ+ community. More concerning is that the “gender-based focus” included in the accords is now associated in the minds of some Colombians with the deterioration of family values, a notion which is not only entirely false but extremely harmful to the LGBTQ+ population.

The backlash against the “gender-based focus” has had serious repercussions, not only in terms of the weakened implementation of the gender provisions of the accord, but also regarding the protection of sexual and gender minorities.

Colombian LGBTQ civil society organizations consulted with have noted that the rights of sexual and gender minorities continue to be under attack, pointing to the appointment of Minister of Interior Nayid Abu Fager Saenz, who blocked the implementation of the public policy meant to protect the rights of the LGBTQ+ populations. They raised concerns over the lack of access LGBTQ+ victims of the armed conflict have to justice mechanisms, given that they are often re-victimized by homophobic public officials.

It is imperative that the Colombian government support the rights of all victims of the armed conflict, refrain from promoting the discrimination of the LGBTQ+ population, and respect and implement the legislation in place and the remaining elements of the peace accords meant to promote this community’s rights. If the Colombian government fails to protect the rights of all the victims, including the rights of sexual and gender minorities, the path to peace will continue to be clouded with distrust and hate.

Laura Cossette and Kenia Saba Perez are recent graduates from the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service with a Master of Arts in Latin American Studies. They have both lived, worked, and studied in Colombia, where they became interested in the topics of peace, gender, and post-conflict reconstruction. As part of their Masters requirements, they completed a Capstone Project in collaboration with the Latin America Working Group Education Fund (LAWGEF) and the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) focused on the implementation of the gender provisions within the Colombian peace accords. As part of this project, they consulted with 10 representatives from Colombian women and LGBTQ+ civil society organizations in order to discern which issues these groups currently consider the most important to achieve a gender-sensitive implementation of the peace accords. Using these consultations as well as extensive secondary research, they co-authored a policy memo to establish recommendations for U.S. policymakers to best support the peace accords, as well as two blog posts on women and LGBTQ+ rights and perspectives on the Colombian peace process.