Authors: Lily Folkerts, Daniella Burgi-Palomino, Emma Buckhout

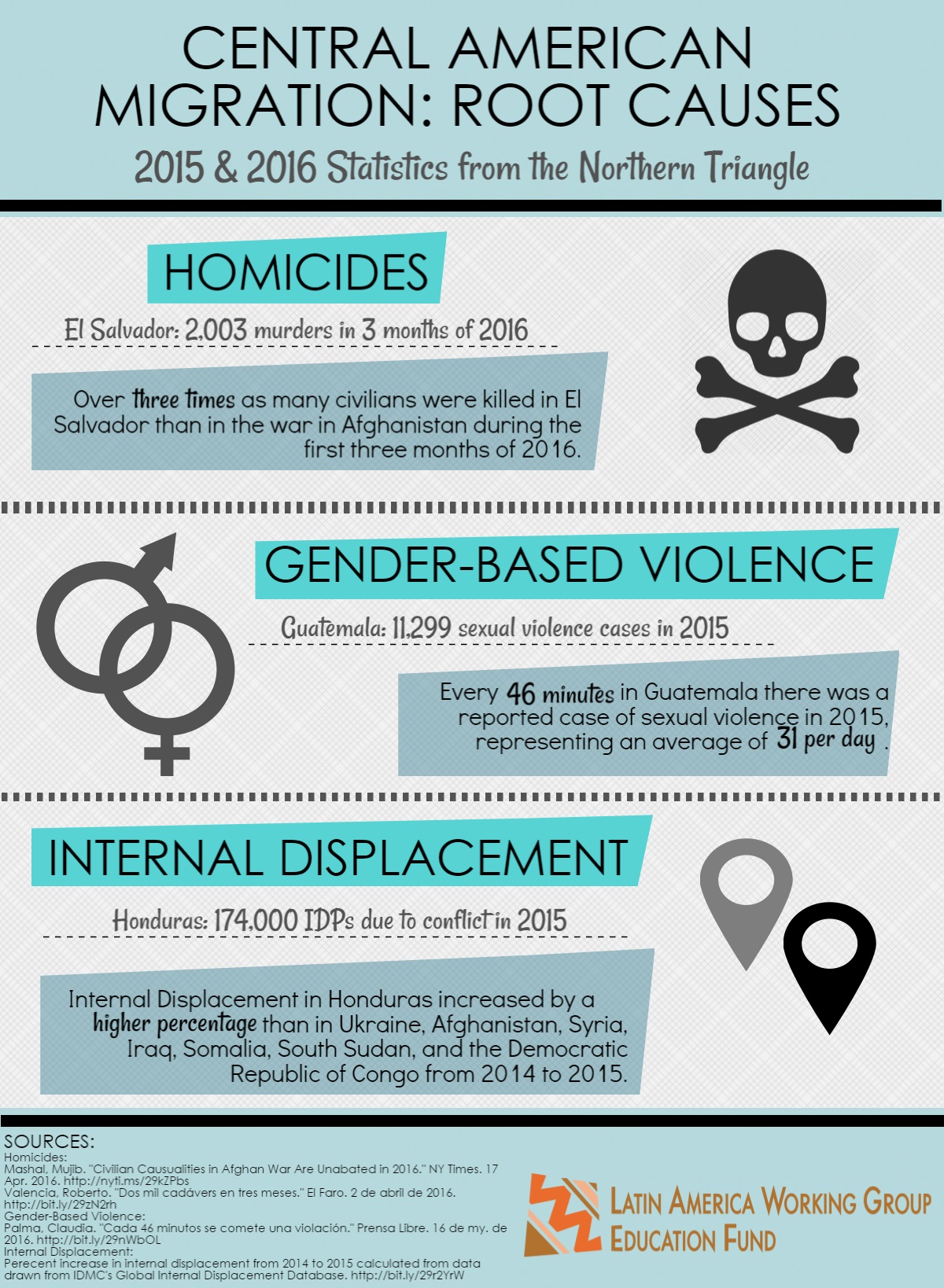

Confronted with alarmingly high homicide rates, gender-based violence, and forced internal displacement, many individuals from the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala have had little choice but to seek safety by migrating abroad in recent years. More than halfway into 2016, sustained high rates of Central American families arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border and seeking protection demonstrate the ongoing severity of regional violence.

|

|

Over two years have passed since President Obama acknowledged the “urgent humanitarian situation” at our border, yet the predominant U.S. government strategy has remained one of deterrence, detention, and deportation. In these life or death situations, U.S. messaging campaigns threatening punitive actions for illegal movement do not act as successful deterrents. The U.S. government has made important strides forward in recognizing refugees in the Central America, but its protection efforts should be expanded to adequately address the breadth of the humanitarian crisis in the region.

Violence from gangs and organized crime, sexual based violence, and internal displacement are a few of many root causes pushing families and children from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador to leave their home countries. Statistics from 2015 and 2016 for each of these areas demonstrate the continuing gravity of these issues.

Homicides

Last year El Salvador had the highest homicide rate in the world, and it appears to be on track to secure that ranking once again. The homicide rate has already increased by an alarming 78% in the first three months of 2016; that amounts to 2,003 total lives lost, with averages of 24 per day in January, 23 per day in February, and 19 per day in March. These sobering numbers expose the hard-hitting reality that nearly every hour of every day a family begins to grieve the loss of a loved one.

| “To the gangs, a life isn’t worth a sandal. I mean, it isn’t worth anything.” – Human Rights Watch interview with Lionel Q. Oct. 2015 |

And Salvadorans aren’t the only ones losing fathers, mothers, sons, and daughters. Although homicide rates dropped 3.6% in Guatemala and 14.6% in Honduras in the first four months of 2016 compared to the same time period of 2015, at respective totals of 1,318 violent deaths and 1,122 homicides, the rates are still much higher than the world average.

In all three Northern Triangle countries, many homicides can be attributed to gangs who use coercion and threats to force membership or demand extortion. In an interview with Human Rights Watch, three teenage boys told their all-too-common stories of how gangs threatened to kill them as well as their families. Midway through the interview, two of the boys lifted their shirts, exposing scars from when they were shot by gang members after refusing to join. For these three boys and thousands like them, fleeing home was not an option but a necessity. No matter how much the U.S. government stresses that undocumented immigrants will be deported, these individuals who fear for their lives will not heed the warning and will continue to come.

Gender-Based Violence

|

|

Femicide rates in the Northern Triangle represent some of the highest in the world among countries not at war, and have increased in recent years. Femicide rates in Honduras increased 263% from 2005 to 2013. Guatemala’s government reported a marked increase in femicides in 2015 and 2016. More recently, the number of femicides in El Salvador has increased 140% during the first third of 2016 compared to the first third of 2015.

Every 46 minutes in Guatemala there is a new victim of sexual violence, amounting to 11,299 reported cases in 2015. In the first two months of 2016, the National Institute of Forensic Sciences of Guatemala (abbreviated INACIF in Spanish) performed 1,104 medical evaluations for sexual crimes against women. With only 15 fewer evaluations this year than in the same time period of 2015, these numbers prove that sexual violence is continuing relatively unabated.

The assassination of René Martínez in the summer of 2016 has brought attention to the high level of gender-based persecution faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) community. On June 1st, the body of Martínez, a leading figure in the LGBTI community in San Pedro Sula, was found disfigured, showing signs of torture. Martínez’s high-profile case is just one of over 170 murders of LGBTI persons in Honduras since 2011.

Within the span of one week this past January, three gay men were killed in El Salvador, sparking calls for investigation into whether these murders were random acts or hate crimes. In 2015, three transgender activists were murdered and one transgender man was brutally beaten—tragedies that prompted legislative action.

Many individuals at high risk for gender-based violence make the difficult decision to emigrate. However, simply beginning the journey does not end the threat of violence. According to a report from migrant shelters in Mexico, the percentage of crimes categorized as sexual abuse or rape of migrants traveling through Mexico increased by 50% from 2014 to 2015. One shelter located in Ixtepec, Oaxaca that participated in the survey reported that 81.8% of transgender migrants are victims of crimes including sexual aggression. Despite these increased risks associated with the journey, continued migration attempts show that circumstances surrounding gender-based violence in the Northern Triangle are so dire that individuals are willing to endure the harrowing journey.

Internal Displacement

|

“I moved out of that community and left my house abandoned… Now I have to start from scratch.”

– Antonio Cruz, interview by La Prensa Gráfica |

Antonio’s community, located in an area being disputed by two different criminal groups, was experiencing violence on a daily basis.On the same day this past year that he abandoned his home in El Salvador, between 12 and 15 other families in his neighborhood felt they had no choice but to do the same. Unfortunately, Antonio’s story is not unique. According to comparisons drawn from a report of the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, a higher percentage of El Salvador’s population was internally displaced in 2015 than in Ukraine, Afghanistan, or the Democratic Republic of Congo.* According to the Civil Society Roundtable on Forced Displacement by Violence and Organized Crime in El Salvador (La Mesa de Sociedad Civil sobre Desplazamiento Forzada por Violencia y Crimen Organizado de El Salvador), 95% of internally displaced respondents that the group assisted from 2014 to 2015 said they were uprooted due to criminal violence.

A similar narrative is unfolding in Honduras, where internal displacement increased from 2014 to 2015 by a higher percentage than in Syria, Iraq, Somalia, or South Sudan.** In total, an estimated 550,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) are fleeing crime in the Northern Triangle. While these statistics are shocking, they are also likely understated. In all three Northern Triangle countries, internal displacement is driven by violence perpetuated by gangs, organized crime and some cases, state actors. Victims deliberately keep a low profile and are reluctant to file reports for fear of retaliation by their persecutors.

El Salvador is a striking example of the complexities surrounding internal displacement. According to Sarnata Reynolds, former senior human rights advisor of Refugees International, the situation of IDPs is further complicated in El Salvador because, “in the majority of countries, once people leave the place that put their lives in danger, they are capable of finding a bit of peace and security. This is not the case for Salvadorans. Due to the fact that the country is so small, and that criminal organizations have such a strong presence at the national level, people do not feel safe and continue living in hiding.”

If safety cannot be obtained in any part of the country, such as in the case of El Salvador, it is no surprise that some internally displaced families make the difficult decision to attempt the long journey to the U.S. As long as violence remains a threat, individuals such as Antonio Cruz and his neighbors will continue to evacuate unsafe neighborhoods and search for options within their home, with the potential to eventually resort to migration abroad.

The U.S. and Regional Response

Physical and gender-based violence and displacement are a few of many factors pushing Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans to flee their home countries. Until these and other root causes of migration are addressed and remedied, victimized individuals and families will continue to seek protection and asylum in the United States, Mexico, or other countries in Central America.

River Suchiate, Mexico-Guatemala border. Photo by Emma Buckhout |

In this scenario, continued deterrence efforts by the Obama Administration, such as the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) messaging campaigns in the region and on Twitter stating that “our borders are not open to illegal migration,” remain ineffective. A recent survey conducted by Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) and analyzed by American Immigration Council reported that Honduran and Salvadoran respondents were aware of the potential dangers of migration and low success rates but did not view them as a deterrent. Regardless of U.S. efforts to curb migration, participants found the dangers of migration and deportation preferable to the crimes and violence they could potentially experience at home.

Two weeks ago, the Department of State announced the expansion of initiatives to address migration challenges through a protection transfer arrangement (PTA), an in-country referral program, and the expansion of the existing Central American Minors (CAM) program. While these steps are encouraging, it is imperative that the United States continue to build upon these efforts to create a more comprehensive response to this humanitarian crisis.

The U.S. government should pursue a comprehensive plan that improves living situations in the Northern Triangle countries by addressing the aforementioned root causes, strongly encouraging governments to address human rights abuses, including those committed by their own police and military, and using resources to prioritize protection, rather than focusing on unsuccessful messaging and harmful enforcement practices that may expose at-risk individuals to greater danger.

* Percentages of internally displaced persons by country populations in 2015 are calculated from data drawn from IDMC’s Global Internal Displacement Database: El Salvador (4.72%); Ukraine (3.75%); Afghanistan (3.61%); Democratic Republic of Congo (1.94%).

**The percentage increase in internal displacement population from 2014 to 2015 by country is calculated from data drawn from IDMC’s Global Internal Displacement Database: Honduras (491.84%); Ukraine (159.51%); Afghanistan (45.84%); Syria (18.18%); Iraq (.30%); Somalia (10.81%); South Sudan (13.13%); Democratic Republic of Congo (45.65%).

Mural in Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías de Córdova office, Tapachula, Mexico.

Mural in Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías de Córdova office, Tapachula, Mexico.