Author: Louis Head

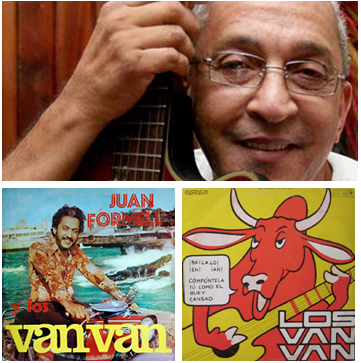

It is difficult to think of an individual whose life’s work represents more on the modern Cuban cultural landscape than composer, bassist, arranger and Los Van Van Director Juan Formell, who passed away May 1, age 71. He will be missed in Cuba, throughout the world, and by me.

It is difficult to think of an individual whose life’s work represents more on the modern Cuban cultural landscape than composer, bassist, arranger and Los Van Van Director Juan Formell, who passed away May 1, age 71. He will be missed in Cuba, throughout the world, and by me.

I’ve traveled to Cuba since the late 70s. My memories are inseparable from the music I’ve heard while I have been there. During my second visit in 1982, I was awakened each day by Sarah González’s “Girón – La Victoria,” celebrating the Cuban victory at the Bay of Pigs. Another number that was constantly in the air was “Tiburón” by Rubén Blades and Willie Colón, a New York salsa tune popular in Cuba – and banned in Miami because of its characterization of the U.S. as a “shark” set to devour “our brother El Salvador.”

And then there was this other number that has remained burned in my brain ever since, “El Baile del Buey Cansao” – “The Dance of the Tired Ox,” by Los Van Van. It was dance music, kinda sorta “salsa,” but unlike anything I had ever heard before. It was this funky thing, to my ears similar to the R&B I had grown up with, complete with a heavy bass line but with this weird, high flying synthesizer going on towards the end of the song.

Pensando bien

El ritmo que tiene

No se ha tocao…

Thinking about it

This here rhythm

Has never before been played…

I noticed Cubans around me taking a pause whenever they heard it. It was obviously a big hit. During the evenings I would see some of them dance to it. I had seen people dance to salsa music, and had seen them dance to son in eastern Cuba. But I had never seen anyone dance the way they did to that song. Their movement suggested to me what the song was about, even if I could barely get the lyrics at the time.

At that point Los Van Van had already been around for thirteen years. I had just heard them for the first time.

***

Born in 1942, Juan Formell was one of the great popular music innovators of the past fifty years. Like Duke Ellington or Miles Davis, his work achieved the difficult feat of remaining cutting edge and relevant throughout his professional career. Formell nurtured dozens of musicians who had stints long and short with his band, and forged legendary partnerships with fellow Van Van members César Pedroso, José Luís Quintana “Changuito,” and Pedro Calvo.

Los Van Van came together in challenging times. In late 1969 just about every resource in Cuba was being directed towards the attempt to harvest ten million metric tons of sugar, with the intention that Cuba would enjoy an economic windfall from record sales. Lots of things stopped happening in Cuba in order to focus on the zafra. Christmas and New Years celebrations were postponed. Professionals and students went to the countryside with machetes that they didn’t know how to handle. Many entertainment activities and venues were closed, including nightclubs where dance music was performed. The music itself was not considered a big priority, and was in fact considered an unnecessary diversion by many.

Cuba, moreover, was promoting the development of a national culture that emphasized the country’s own roots, talent and traditions, particularly at the expense of influences coming from the north. While this was understandable given the centrality to the Revolution of independence from the United States, it followed nearly two centuries during which Cuba’s cultural identity had formed in tandem with that of the U.S. It is no accident that so much American and British rock music from the sixties has a Cuban rhythmic foundation, and it should be no surprise that music from the U.S. would be embedded in the hearts and minds of young Cubans. It continued to be heard, even as North Americans were completely cut off from anything that was happening on the island.

Formell and the musicians that he assembled were part of this broader reality, and they imaginatively fused what they were doing with national imperatives, while drawing on musical skills that are consummately Cuban. The very name of the band was taken directly from a prominent slogan of the time that “los diez millones de que van… van” – “the 10 million must go… go.” The phrase was everywhere and the group’s founders knew that the new name would resonate in the street. Also significant was the date of their first performance – December 4 – el Día de Changó, the Yoruba god of thunder and drums, a very important figure in the Cuban national consciousness.

Los Van Van built its music over a foundation of Afro-Cuban musical traditions and prowess, weaving in elements of North American rock, jazz and R&B. The first edition of the band was a Cuban charanga of strings, flutes and percussion, only with electric guitars, a trap drum set and vocal harmonies reminiscent of doo-wop or the Beach Boys.

Early audiences would at times look on in fascination and not even dance. But in spite of unfavorable early press reviews, the band captured the attention of the Cuban public and never let it go. By the mid-70s Los Van Van had created a completely new style. Formell called it songo. This was the next stage of Cuban dance music – coming on the heels of the mambo, cha-cha-cha and pachanga – and it was made by and for a new Cuba. By the 1990s when greater numbers of people in the U.S. began to hear from Cuba again, Formell and his Van Van had, along with Chucho Valdés and Irakere, laid a foundation for the intelligent and explosive music that burst forth from the island, eventually taking on the name timba.

While Formell would tell you that the dancers came first, storytelling followed right behind. From 1969 on Los Van Van would record songs that reflected Cuban reality by chronicling everyday life on the island, building upon a tradition, as old as Cuban identity, of troubadours and popular music singers and songwriters like Miguel Matamoros, Ignacio Piñeiro, Ñico Saquito and Arsenio Rodríguez. Los Van Van developed a deep and organic relationship with not only dancers but the entire country. In the process, Formell made an important contribution to defining the role of the Cuban artist within the realm of culture, that key space within Cuban civil society in which so many of the country’s inner dialogues have taken place. Like Yoruba-derived religion in Cuba, Formell’s chronicles accomplished this “hiding in plain sight,” especially from foreign observers unable to decipher what Cuba is about.

So while the 1976 song “Resuelve” is about love, its underlying message is the need for resourcefulness in resolving everyday challenges, and to take things in stride and make the right decisions. “Que Palo Es Ese,” released in 1983 and one of the more overtly “political” numbers the band ever did, was about the fight against U.S. intervention in Central America – and also lifted up in a sneaky (and thus appropriate) way the Congo-derived religion regla de palo. The 1985 hit “La Habana Sí” exhorted residents of that city to join in efforts to make it “the most beautiful capital in Latin America.” 1987’s Titimanía meanwhile played with older men who attempt relationships with younger women, and carried an implied critique of those who would rather take a day off at the beach than do their work.

The socialist camp collapsed at the end of the 80s, and the last oil tanker from the Soviet Union called to port in Havana in 1991. When the oil was gone, the lights literally started going out in Cuba. After over a decade of relative prosperity, a severe economic crisis set in, so bad that many did not even have enough to eat. Formell and Los Van Van continued as they had from the beginning, reflecting the resilience of the people, who were now making major life adjustments. References to Afro-Cuban religion increased, most notably in the song “Soy Todo,” known popularly by its refrain ay díos amparame – God Protect Me – adapted by Formell from a poem by the Havana poet Eloy “El Ambia” Machado. “Un Socio” – A Business Partner – meanwhile described how the new economic reality of the Special Period was changing people’s lives, and poked ironic fun at the fact that folks did not have a lot of practical experience at making their way in a new entrepreneurial environment.

“I don’t think there’s a better living record of Cuba during these years than that left to us by Los Van Van,” author and musicologist Ned Sublette stated to me the other day. Sublette, who spent a lot of time in Cuba during the 90s working with Cuban musicians and their music, knew Formell and his orchestra well.

“Van Van’s work has sustained a respectful dialogue with the Cuban Revolution, beginning with their very name, and allowed for the creation of a body of work that helps us understand a whole lot better not only this period but that throughout the band’s existence,” says Sublette.

That respectful dialogue was precisely what earned Formell the hatred of some in the exile community. I have had the fortune to see Los Van Van perform on many occasions, but perhaps the most impactful was when they made it to Miami for the first time in 1999 to perform, in the face of violent opposition to their presence.

It has never been easy for modern-era Cuban musicians, or other professionals for that matter, to enter the U.S. to perform or work. Moreover, Cuban exiles have always identified Van Van with the Cuban government. In 1999, a courageous Miami-area producer was able to present the band, after successfully outmaneuvering City of Miami officials and exile groups that threw a slew of impediments in the way. The Miami-area press burned. Cuban exile AM stations went into full gear calling for a boycott, and for action. Concertgoers had to pass through a gauntlet of an unforgettably hostile crowd that threw eggs, stones and epithets at us as we entered the venue. The Miami police were there – protecting the mob that was assaulting us.

But the tranquility inside the arena was equally unforgettable, as was the emotional performance by the band, later released as the DVD Van Van Live at Miami Arena. The thousands outside were Cubans seemingly twice removed from the thousands of Cubans inside. The voices of the latter continue to be heard today as part of calls for a different U.S. attitude and policy toward the island. That Miami appearance was one of many triumphs for Juan Formell.

Last week, a reader in Cuba put it this way in an online comment to an article on Formell that appeared in the Cuban daily Granma:

“We grew up with the music of this master, the same music with which he defended our country.”

I figure that to be a good clue as to how he will be remembered over time in Cuba.