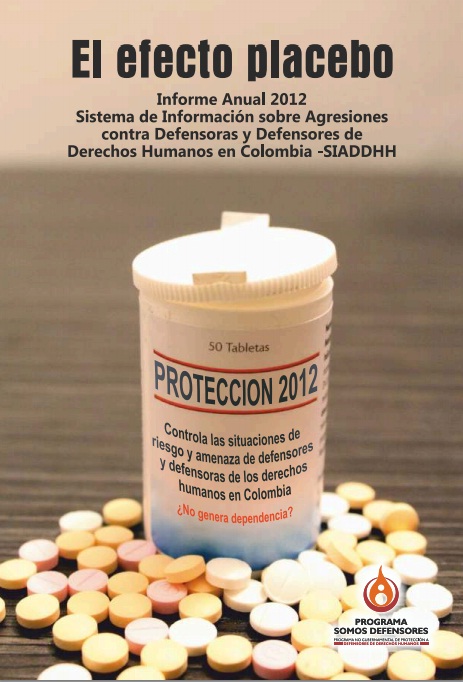

“What is going wrong in Colombia?” asks the coalition of human rights defenders in Colombia. The government of Juan Manuel Santos last year invested time and funding in mechanisms to protect communities and people at risk, among them human rights defenders.

And yet, in 2012, every five days a defender was assassinated in Colombia, and every 20 hours one defender was attacked. In 2012, 357 men and women in Colombia were attacked for their work as human rights defenders, according to Somos Defensores (“We Are Defenders”), which maintains a unified database of attacks against human rights defenders. Sixty-nine defenders were assassinated, a jump from 49 assassinations in 2011. Indeed, this is the highest number of aggressions against defenders registered by the database in the last ten years, and a 49 percent increase since 2011. The attacks include: 202 threats, 69 assassinations, 50 assaults, 26 arbitrary detentions, 5 forced disappearances, 1 arbitrary use of the penal system, 3 robberies of information, and 1 case of sexual violence…

“Is it possible that protecting leaders and defenders goes beyond providing bulletproof vests, bodyguards and laws that sit unused on top of the desks of ineffective government officials?” Somos Defensores 2012 annual report.

Somos Defensores 2012 annual report.

There were efforts to improve and expand the coverage of the protection program in the last year, according to Somos Defensores. This was driven by substantive discussions in the National Roundtables for Guarantees between local and national human rights and social organizations and government officials. In 2012, the government’s National Protection Unit received 9717 requests for protective measures, of which 3668 were approved. There was little progress in implementing collective protection measures, however, which are essential for returning communities, Afro-Colombian, indigenous and other communities at risk. Contingency plans were developed for various zones by the Interior Ministry but not a single one was implemented; according to the Ministry, local authorities are responsible for implementation.

There were advances in 2012 in judicial rulings regarding the protection of defenders, including a Supreme Court ruling that crimes against defenders or land rights leaders should be considered crimes against humanity, given a context of systematic persecution. Other advances included: the network of international agencies in Colombia established a National Prize for Defending Human Rights in Colombia, and the government pledged to launch a media campaign on the rights of defenders in 2013.

But the sad truth is: even if protection plans were fully implemented, no amount of protection can make up for the lack of progress in investigating and prosecuting attacks against human rights defenders. Three agencies that should help the most in defending defenders–the Attorney General’s office, the Ombudsman’s Office (Defensoría del Pueblo), and the Inspector General’s office (Procuraduría General) were “absent” in 2012. In particular, “it is discouraging that after 8 long years of silence from the administration of Volmar Antonio Pérez [the Ombudsman], we hoped for a positive change, but it did not happen.”

The 69 defenders who lost their lives include indigenous leaders, people involved in organizing over mining companies, hip-hop musicians who organized against violence, youth leaders, community organizers, heads of victims’ associations, land rights crusaders, union organizers, Afro-Colombian leaders, the organizer of a women’s handicraft cooperative and an LGBT defender. Of the 69 murders, 9 are believed to have been committed by paramilitaries, 11 by the FARC guerrillas, 1 by the armed forces, and the vast majority are unknown. This represents an increase of assassinations attributed to the FARC compared to the 5 believed to be committed by this guerrilla group in 2011.

Defenders were threatened by phone, visits to their homes, and distribution of threats via pamphlets, flyers, emails and text messages. Paramilitary successor groups such as the Black Eagles, Rastrojos and Urabeños were behind the majority of threats.

Of all types of aggressions against defenders in 2012, paramilitaries were believed to be responsible for 41 percent; guerrillas for 9 percent; the Colombian government (army, police, intelligence, Attorney General’s office, etc.) for 13 percent; and 37 percent were unknown.

Somos Defensores notes that some of the increase in aggressions listed in the database may be due to the greater determination of the human rights community in Colombia to document abuses against them despite their fears.

The year 2012 was “an endless round of meetings, workshops, encounters, studies, cell phones for protection, bullet proof vests, bullet proof cars, bodyguards, arms and conferences to debate the eternal situation of insecurity and persecution of a legal and legitimate exercise of rights that each day costs more lives in Colombia, but without attacking the real causes of the violence against human rights defenders in Colombia: the lack of investigations, and the real prevention of aggressions, impunity, corruption, stigmatization, and the abandonment of many leaders in regions of the country that are handed over to the control of armed actors, corrupt politicians and multinational corporations.”