Author: Daniella Burgi-Palomino

Editor’s Note: This is the second part of a series by Latin America Working Group Education Fund on the intersection of human rights, migration, corruption, and public security in Honduras and El Salvador. You can find the full series here.

Isabel was pregnant with her third child when she was warned by her cousin that she was in danger. Members of the Barrio 18 gang followed her to her children’s school to assault her and to tell her that she had an hour to turn over items she had supposedly stolen or else she was going to be killed. Isabel had no idea what they were talking about. Isabel walked home that day to tell her mother what had happened. Her mother told her to flee and leave her neighborhood immediately. A few days later, she left her kids with her ex-husband and fled to Guatemala.

– Translated and summarized from Revista Factum, “La historia de una mujer sin país”

A dozen members of MS-13 came by to threaten Francisco and his family, beating him and his wife, telling them that they had gotten involved in something that wasn’t their business and that they had to pay for it now. The threats came just days after Francisco had helped one of his church friends flee because of similar threats. Francisco and his wife didn’t even consider fleeing to another town. For them, that wasn’t an option. They knew it would only prolong the inevitable. Two days later, they left their house with a suitcase at 2 AM to begin their journey to leave the country. Before crossing the border, the journalist covering the story asked Francisco’s wife what she thought a country without gangs would be like. “It will be like a dream. To be honest, I can’t even imagine it,” she said.

–Translated and summarized from Revista Factum, “Una familia huye del país de las pandillas”

For people like Isabel and Francisco in El Salvador and Honduras, fleeing first implies leaving their homes and seeking safety within the country. Internal displacement is often the precursor to international migration and means a life in hiding with fear and trauma and without protections.

In mid-2017, LAWG heard that the levels of internal displacement due to violence were substantial and ongoing in both countries. In this blog, we unpack recent statistics and explain what continues to drive this forced displacement of people, what it means to live a life in hiding in particular for women and children, and the lack of government policies to respond to internally displaced persons (IDPs) in El Salvador and Honduras.

Same Actors, Heightened Fear in the Face of Violence

Honduras

In 2013, the Honduran government recognized that the country faced a crisis of internal displacement and collaborated with the UN Refugee Agency and civil society representatives to take a look at the scale of the problem. The Inter-Institutional Commission for the Protection of Persons Displaced by Violence published a first study on internal displacement in the country in 2015 and found that 174,000 people were internally displaced in the 20 municipalities surveyed between 2004 and 2014.[1]

|

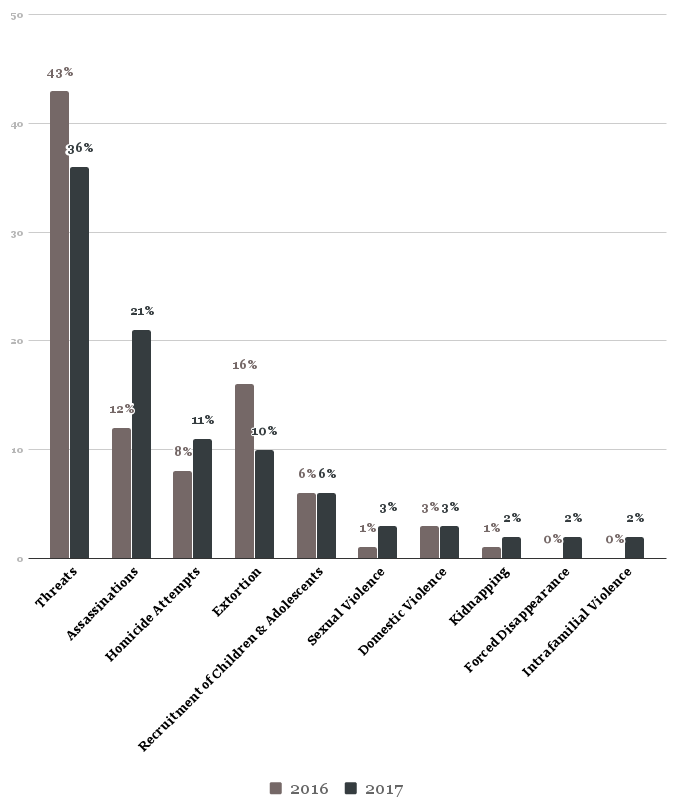

Top 10 Reasons for Forced Displacement in Honduras,

January-May 2016 vs. 2017 |

|

|

Source: Statistics obtained and translated from the National Commission on Human Rights, CONADEH, Boletín Estadístico Sobre el Desplazamiento Interno, Comparativo 2016-2017 de Enero a Mayo, junio de 2017, 3, http://bit.ly/2A4txQc.

|

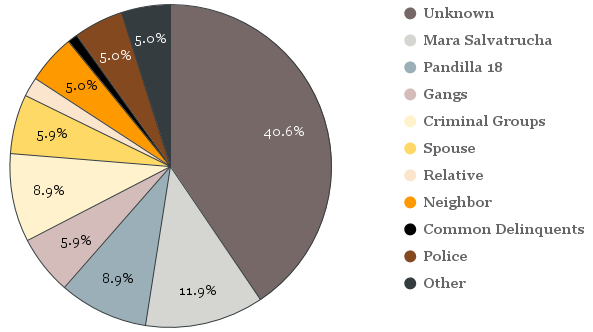

The main difference among the cases registered by the local CONADEH offices in 2017 was that a higher number of individuals were less willing to name the perpetrator behind their forced displacement—suggesting a context of heightened fear in the face of the same acts of violence. International humanitarian organizations, like the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), also reported that in about 50 percent of the cases of internal displacement they registered from the end of 2016 through the beginning of 2017, individuals chose not to identify the perpetrator. [3] In a country with high impunity rates reflected in the fact that only 4 of every 100 homicides results in a conviction, [4] it is not surprising that people would be hesitant to report the aggressor behind the forced displacement for fear of retribution or persecution. It also speaks to the level of territorial control exercised by gangs and organized crime in some areas of Honduras. [5] Overall, gangs like the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and the Pandilla 18 continue to drive internal displacement as in 2016, though organized crime and the police were identified in a higher number of cases compared to last year according to CONADEH statistics.

We also heard that “mano-dura” strategies to combat gangs in urban areas through “operaciones de saturación,” or aggressive, targeted raids carried out by anti-gang units, contribute to internal displacement–pushing out entire families and driving gang members to rural areas where they did not previously have a presence, in turn affecting the stability of communities in those rural parts of the country. [6]

The risk of displacement from resisting large-scale development projects was also something we heard about in Honduras and, though documented to a lesser degree, is reflected in recent CONADEH and United Nations reports. [7] “The government’s extractivist model drives migration,” one environmental activist told us. [8]

| Honduras: Perpetrators Behind Forced Displacement, January-May 2017 |

|

| Source: Statistics obtained and translated from the National Commission on Human Rights, CONADEH, Boletín Estadístico Sobre el Desplazamiento Interno, Comparativo 2016-2017 de Enero a Mayo, junio de 2017, 3, http://bit.ly/2A4txQc. |

El Salvador

In El Salvador, the government has yet to recognize the crisis of internal displacement. In 2015, the nongovernmental International Rescue Committee estimated that the number of displaced individuals was approximately 324,000, or 5.2 percent of the country’s population, but the crisis remains insufficiently documented. [9] Since 2014, the Civil Society Working Group on Internal Displacement and its thirteen NGO members are the only groups in the country documenting cases, and six of them also provide accompaniment to victims of internal displacement. Some individual government agencies, like the Ombudsman Office for Human Rights (Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos), have recognized the crisis within the country, [10] but the position of the national government has not changed in the past three years despite multiple testimonies that show no improvement of the situation. [11]

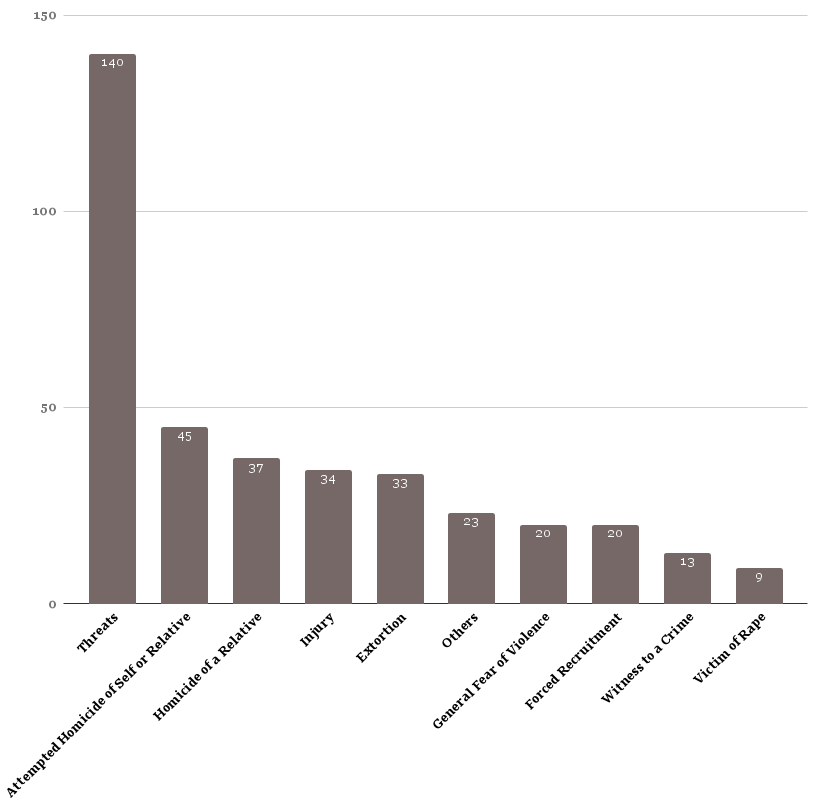

In the first nine months of 2017, the Salvadoran NGO Cristosal documented 83 cases, representing 394 individuals as victims of forced displacement, already higher than all of 2016. [12] Among these, the two most common reasons behind forced displacement early this year were attempted homicide or the homicide of a relative. Half of the cases documented did not report their cases to authorities, citing fear of what would happen and lack of trust in government officials as the reason. The Civil Society Working Group on Internal Displacement reported a 54 percent increase in the cases documented during the first half of 2017 compared to the same time period in 2016. [13] From August 2014 to December 2016, the working group documented a total of 339 cases, representing 1,322 victims, or 699 in 2016 alone. [14]

| Top 10 Reasons for Forced Displacement in El Salvador, 2016 |

|

| Source: Mesa de Sociedad Civil contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en el Salvador, Desplazamiento Interno por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en El Salvador, 45, 2016, http://bit.ly/2A2kZtc. |

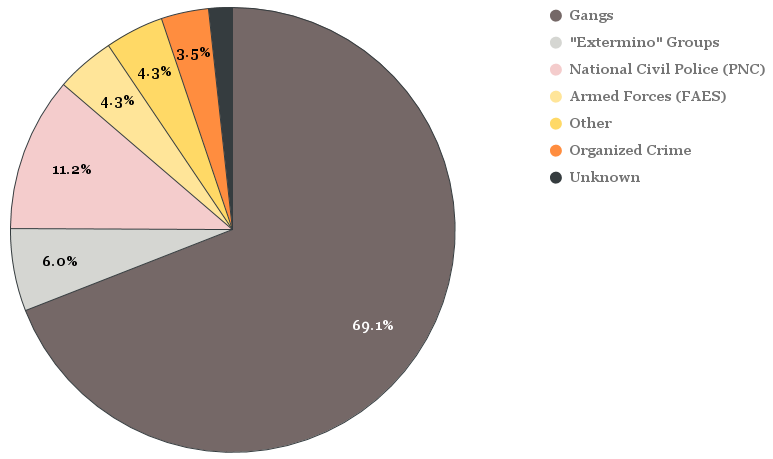

Reports from the Civil Society Working Group on Internal Displacement from 2015 and 2016 have consistently pointed to gangs (Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18) and organized crime as the main drivers of forced displacement–a pattern we heard again during our trip in mid-2017. [15] We heard of an increased level of territorial control by gangs, impacting the degree to which organizations felt comfortable in assisting victims and denouncing crimes at a local level. “We have to maintain a low profile and have had to leave some areas because of the level of gang control,” NGO staff told us. [16]

State security forces including the police (Policía Nacional Civil) and the armed forces (Fuerzas Armada de El Salvador) were also named as actors behind forced displacement in the country. In particular, police in anti-gang units and shadowy “exterminio” groups, which may include members of the police or soldiers, were also cited by NGOs as driving a sense of fear in communities and contributing to forced displacement. [17]

| El Salvador: Perpetrators Behind Forced Displacement, 2016 |

|

| Source: Mesa de Sociedad Civil contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en el Salvador, Desplazamiento Interno por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en El Salvador, 47, 2016, http://bit.ly/2A2kZtc. |

Life in Hiding: Impacts of Violence and Displacement on Families and Children

The sole condition of being forced to leave one’s home because of violence increases a person’s vulnerability in all aspects of their daily life. Often, displacement is not the first time a person is threatened, but rather it is the culmination of multiple threats and incidents of violence over time to an individual or family–the last straw in a series of events at which point the need to escape becomes a survival strategy and doing it in a way that won’t increase danger, the challenge. Honduras is a larger country than El Salvador, and so the possibility to hide from gangs exists, even if to a very limited degree and only temporarily. In El Salvador, the opposite is true; “there is no place to hide in El Salvador, so people leave,” a senior government official told us. [18]

Many of the cases documented by the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of IDPs during his visit to Honduras were that of individuals leaving overnight and without notice. [19] In El Salvador, the same is true. Multiple testimonies show individuals and families being given 24 hours to flee their homes by gangs. [20] This usually implies that an individual or family will leave with the bare minimum, what they can carry with them and nothing more. In one recent survey in Honduras, clothing was identified as one of the most urgent needs of IDPs, alongside a lack of understanding of their rights, followed by the need for food and identification documents. [21] Property is also sold very cheaply or simply left behind. Abandoned houses are often taken over by gangs for strategic control and illicit activities and are almost never recovered. [22]

People at risk frequently turn to families and friends in other cities or towns first for safety, which in turn can place additional challenges on relatives with already limited resources–pushing families into a cycle of poverty, displacement, and violence. [23] Displacement also means most of those affected will lose their livelihood or diminish their source of income substantially. Many IDPs turn to informal activities, such as begging or temporary work, or increase their reliance on savings or remittances sent by relatives. [24] In many cases, one of the reasons for the displacement could have been the targeting or extortion of someone because of their job to begin with—for example, a street vendor or shop owner.

Internal displacement usually implies a life in hiding, trauma, and deep uncertainty. These impacts are intensified for women, LGBTI individuals, youth, and children. Women heads of households who are displaced with their children often have less of a network of families and friends to turn to, placing them at a greater risk in their search for safety. [25] Displaced women who are alone are more vulnerable to sexual abuse, violence, and trafficking. [26] LGBTI individuals also are at heightened risk for displacement and, once displaced, are subject to abuse and violence. [27] An organization working with trans-women told us that this population has no idea about their rights in the face of rights violations they experience. [28] Trauma is compounded by the lack of medical and psychological services for IDPs–forcing a victim to carry the trauma of violence with them.

The impact of violence on children is particularly egregious in both countries. Many families make the decision to move because of threats to recruit or target their children by gangs. During her recent visit to El Salvador, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of IDPs reported how she heard from many young people that “it is a crime to be a young person in El Salvador today.” [29] Children continue to make up a significant percentage of the victims of gang violence in both countries. In El Salvador, 540 children were murdered in 2016 according to an official government report. [30] In Honduras, we heard of an increase of massacres or multiple homicides of youth and children through the first six months of 2017. [31] “The government does not include young men between 16 and 24 years old in any protection agenda even though they are among the most vulnerable, and so they end up seeking protection with gangs because they can’t find it anywhere else,” one NGO representative in El Salvador told us. [32] Others simply disappear in their process of hiding from danger. “They don’t want to be found,” NGOs told us.

The consequences of violence are visible in the percentage of IDPs who are children and youth. In Honduras, in the last ten years, there have been more than 78,000 displaced children under the age of seventeen, or 43 percent of the total displaced population. [33] Similarly in El Salvador, according to the cases tracked by the Civil Society Working Group on Internal Displacement between 2015 and 2016, the top age groups of both males and females affected by internal displacement were children or youth through the age of 25. [34]

Dropout rates in schools are one of the main indicators of the toll this violence takes on children. Children stop attending school because gangs exert control over schools and because of the increase of threats–all of which also forces them to leave and go into hiding. In Honduras, at least one child in every household in the most violent areas of the country did not attend school as recently as 2016. [35] In El Salvador, numerous reports have confirmed confinement as another way of life for children, in particular girls, to avoid the daily harassment and violence from gangs at schools and in their neighborhoods. [36] In some instances the violence is so bad that schools have had to cancel sessions due to threats. Displaced children are forced to transfer schools, but this implies additional costs for parents and maneuvering through school bureaucracy and weak infrastructures, and all too often not attending school becomes a permanent reality. [37]

Because of the influence of multiple threats in a family’s decision to flee, separation sometimes becomes a strategy for survival. [38] One family member may leave behind the rest in hiding, resulting in the separation of families. This in turn affects the social fabric of a community little by little as more families have to leave and sometimes entire neighborhoods are disintegrated.

Not all IDPs will make the decision to migrate internationally. Often, this decision is dependent on the individual or family’s level of resources or family network in safe locations. In the instances where families and individuals may not have the resources to flee, despite the degree of risk, they may confine themselves to being locked up–a prisoner in their own homes, to avoid danger. Often, however, internal displacement has been documented to be a strong precursor to international migration. Among the cases documented by the Civil Society Working Group on Internal Displacement in its latest report, 88 percent said their intention was to leave the country and of those, 60 percent said they would do it in a clandestine manner. [39]

For individuals, or in particular children, whose immediate protection network is in the United States, they will turn to them for safety. “The government calls it family reunification, but it’s just a search for safety. When the government doesn’t provide protection, individuals turn to their families and, if they are in the United States, then that is where they will go,” one NGO staff member told us. [40]

No One to Turn to: Lack of Government Responses

The difference in official government recognition of the situation of internal displacement in Honduras and El Salvador matters little when it comes to actual responses to IDPs. In both countries, by and large, IDPs remain an invisible population, their rights still ignored.

Honduras

Though it’s been three years since the government has officially recognized the situation of internal displacement, this has not yet translated to effective state policies and programs to respond to IDPs.

In August 2016 and in collaboration with the UNHCR, the government created a Unit for Internal Displacement (Unidad de Desplazamiento Forzado or by its acronym in Spanish UDFI) under the National Human Rights Commission with five local centers across the country. [41] These units are an incipient step to tracking cases and have resulted in some indicators of the identification of patterns and profiles of cases of internal displacement. Complaints are received at a local level and, in some instances, cases in immediate danger are channeled to the UNHCR who in turn attempts to find a temporary solution, safe shelter, or emergency humanitarian evacuation for the individual or family at risk. However, the numbers of cases received are still small compared to the estimated numbers of IDPs in the country. Other humanitarian organizations, like the NRC, have documented a lack of government responses to cases of internal displacements that they have accompanied and which have been brought to authorities. In one of their recent reports, they indicated cases where government officials went so far as to state that IDPs were not a priority population they needed to respond to. [42]

Besides the small stopgap measures of international humanitarian organizations to find temporary solutions including safe shelter or emergency evacuation for individuals and families, there is still no comprehensive framework to provide IDPs with durable solutions in Honduras. Governmental agencies focused on women, children, and access to education have not yet adapted their programs for IDPs, leaving a population that cannot access basic services.

The Inter-Institutional Commission for the Protection of Persons Displaced by Violence has been working on a draft law to address the situation of internal displacement in the country, but the process with the Honduran Congress has been slow. The proposed law would set up a National Internal Displacement System with local centers to provide direct attention to IDPs, register and track cases, and allow individuals to recover and protect abandoned property and assets. However, it is unclear what version of such a proposal will be passed. Moreover, if passed, such a system would require the commitment of a substantial budget, capacity-building for authorities, and collaboration mechanisms between government agencies in order to function effectively.

El Salvador

In El Salvador, IDPs remain largely invisible, and the government has focused its response on refusing to acknowledge the problem and promoting weak frameworks that on paper, aim to address victims of violence but in practice, fail to do so.

The 2014 widely consulted Plan El Salvador Seguro, the government framework meant to outline responses to violence, has a strong focus on victims of violence as one of its pillars. As a part of this, in February 2017, four municipal offices were opened in some of the municipalities with the highest indicators of violence to provide attention to victims (OLAVs or Oficinas Locales de Atención a Victimas). [43] However, these offices have minimal staff and resources to carry out their work. Their work remains incipient; they have not yet focused on the prevention of violence, and they lack coordination with other governmental agencies that focus on addressing the needs of specific populations, such as National Council for Children and Adolescents (CONNA), the Institute for Children & Adolescents (ISNA), and the Salvadoran Institute for the Development of Women (ISDEMU).

A senior Salvadoran government official from the Ombudsman’s Office admitted to us that there are no governmental programs to assist IDPs in the country and that only NGOs do this work. [44] Despite this recognition from some government officials, others have turned to denials of the statistics on internal displacement that international humanitarian organizations have published and even going as far to state that IDPs are “taking advantage of their situation.” [45] Yet, camps set up for IDPs, such as one in the municipality of Caluco, Sonsonate last year where approximately 25 number of families were housed, refute the fact that internal displacement is not an issue in the country. [46]

Until the Salvadoran government recognizes the problem officially and adapts its policies to acknowledge the particular situation of IDPs as victims of violence, temporary stopgap and emergency humanitarian responses implemented by NGOs remain the only measures responding to IDPs. And even these are insufficient. Often, they simply lengthen a process by which an individual must remain in hiding and without access to their rights or protections, “privado de libertad,” living a life without safety and dignity.

On her recent trip to El Salvador in August 2017, the UN Special Rapporteur for the rights of IDPs noted that the government’s current legal approach is focused on addressing the illegal restriction on the freedom of the movement of people and illegal occupation of property, failing to acknowledge the impact of internal displacement on the lack of protections faced by those displaced. To this end, a very recent decision by the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of El Salvador is an interesting development as it orders the Minister of Justice and Public Security and other governmental agencies to take measures to protect an extended family of thirty people who had been displaced earlier this year by the Barrio 18 gang. [47] The family had presented numerous complaints regarding the state’s failure to protect them. Still the decision is just temporary measure and not yet a legally binding precedent to address the broader crisis in the country. The IACHR made reference to the precedent but also on the remaining need of the state to “recognize and adopt measures to prevent displacement, as well as to protect the human rights of those who have been forced to leave their homes.” [48]

Man walking on road in rural community outside San Salvador, El Salvador. Photo by Daniella Burgi-Palomino

Increasing levels of internal displacement are a recognition that Honduras and El Salvador continue to suffer a serious situation of insecurity and that their governments have failed to protect its population in the face of the violence. While official recognition is a first step, both governments must significantly strengthen their efforts to find durable solutions for IDPs; including implementing integral, well-funded national systems that track and address the needs of men, women, adolescents, and children who are displaced and provide them with shelter. Governments, together with international organizations, must build the capacity of government authorities to reform existing policies, programs, and institutions to ensure efficient responses to IDPs as an important subgroup of victims of violence.

The crisis of internal displacement in El Salvador and Honduras could be compounded by the return of deported migrants from the United States in the future. An additional wave of men, women, and children without options to live a life in safety in their communities will fuel more internal displacement and out-migration and test the capacity of the international organizations and NGOs already overwhelmed with doing their best to find solutions for people in danger. With the phasing out of the Central America Minors (CAM) program ending any option to access international protection and apply for refugee admissions to the United States from these countries, families and children will remain invisible and displaced, not only within their countries but in the journey they will be forced to make to the United States and other countries to seek safety.

[1] Comisión Interinstitucional para la Protección de Personas Desplazadas por la Violencia, Characterization of Internally Displaced Populations in Honduras, 12, November 2015, accessed October 26, 2017, http://www.jips.org/system/cms/attachments/1050/original_Profiling_ACNUR_ENG.pdf.

[2] Comisionado Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (CONADEH) and Defensoría Nacional de las Personas Migrantes, Pueblos Indígenas y Adulto Mayor Unidad de Desplazamiento Forzado Interno (UDFI), Boletín Estadístico Sobre el Desplazamiento Forzado Interno: Identificación de Casos en los Registros de Quejas en Cinco Oficinas del CONADEH, 2, June 2017, accessed October 26, 2017, http://app.conadeh.hn/descargas/Boletin%20Estad%C3%ADstico%20UDFI-CONADEH.pdf.

[3] Norwegian Refugee Council, Reporte Honduras Desplazamiento (n.p., 2017), 4.

[4] United Nations General Assembly, Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the human rights situation in Honduras, report no. A/HRC/34/3/Add.2, 5, February 9, 2017, accessed October 30, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/G1702929.pdf.

[5] United Nations Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, 4 and 6, April 29, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G16/068/68/PDF/G1606868.pdf?OpenElement.

[6] LAWGEF Interview with UNHCR Honduras Protection Officer, Tegucigalpa, Honduras, July 27, 2017.

[7] United Nations Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons on his Mission to Honduras, 4, April 5, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G16/068/68/PDF/G1606868.pdf?OpenElement.

[8] Interview with environmental activist, Tegucigalpa, Honduras, July 27, 2017.

[9] Crisis Watch, Millions on the Move Displacement around the world continues to reach record levels, as millions risk their lives for safety, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, http://crisiswatch.webflow.io/.

[10] Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos de El Salvador, Informe de Registro de la Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos sobre Desplazamiento Forzado, 7, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5784803ebe6594ad5e34ea63/t/57d0bb996a496397948bd06c/1473297311066/Informe+oficina+ombudsman+desplazamiento+forzado+en+El+Salvador+%281%29.pdf.

[11] Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos de El Salvador, Informe de Registro de la Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos sobre Desplazamiento Forzado, 13, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5784803ebe6594ad5e34ea63/t/57d0bb996a496397948bd06c/1473297311066/Informe+oficina+ombudsman+desplazamiento+forzado+en+El+Salvador+%281%29.pdf.

[12] Defensores, “Tercera misión de observación de derechos humanos a Honduras,” Defensores en Línea (Tegucigalpa, Honduras), September 8, 2017, http://defensoresenlinea.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017-Informe-espa%C3%B1ol-Foro-Honduras-Suiza.pdf.

[13] Cristosal, “UN Expert on Internal Displacement Visits El Salvador,” last modified August 21, 2017, accessed October 26, 2017, http://www.cristosal.org/news/2017/8/21/un-expert-on-internal-displacement-visits-el-salvador and updated with information provided electronically on October 30, 2017 by Cristosal staff.

[14] Mesa de Sociedad Civil contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en el Salvador, Desplazamiento Interno por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en El Salvador, 35 and 45, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5784803ebe6594ad5e34ea63/t/5880c66b2994ca6b1b94bb77/1484834488111/Desplazamiento+interno+por+violencia+-+Informe+2016.pdf.

[15] Mesa de Sociedad Civil contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en el Salvador, Informe sobre Situación de Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia Generalizada en El Salvador, 4 and 47, accessed October 26, 2017, http://sspas.org.sv/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Informe-2015-Situacion-de-Desplazamiento-Forzado.pdf.

[16] Interview with staff member from women’s organization, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 28, 2017.

[17] Interviews with multiple NGOs, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 28-August 2, 2017.

[18] Interview with official from Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos de El Salvador, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 28, 2017.

[19]United Nations Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons on his Mission to Honduras, 9, April 5, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G16/068/68/PDF/G1606868.pdf?OpenElement.

[20] Salvador Meléndez, “Los Desplazados Invisibles” [The Invisible Displaced], FACTum, December 5, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, http://revistafactum.com/los-desplazados-invisibles/.

[21] Norwegian Refugee Council, Reporte Honduras Desplazamiento (n.p., 2017), 5.

[22] James Fredrick, “Gangs Drive Hondurans from their Homes and Land,” UNHRC The UN Refugee Agency, last modified September 8, 2017, accessed October 26, 2017, http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/stories/2017/9/59b10d4f4/gangs-drive-hondurans-homes-land.html.

[23] Norwegian Refugee Council, Reporte Honduras Desplazamiento (n.p., 2017), 6.

[24] Mesa de Sociedad Civil contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en el Salvador, Desplazamiento Interno por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en El Salvador, 54 and 58, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5784803ebe6594ad5e34ea63/t/5880c66b2994ca6b1b94bb77/1484834488111/Desplazamiento+interno+por+violencia+-+Informe+2016.pdf.

[25] Norwegian Refugee Council, Reporte Honduras Desplazamiento (n.p., 2017), 4; and United Nations Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, 13, April 29, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/G1608880.pdf.

[26] United Nations Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, 10-11, April 29, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/G1608880.pdf.

[27] United Nations Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, 10-11, April 29, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/G1608880.pdf.

[28] Interview with staff member from women’s organization, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 28, 2017.

[29] United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Statement on the Conclusion of the Visit of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, Cecilia Jimenez-Damary to El Salvador – 14 to 18 August 2017,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, last modified August 18, 2017, accessed October 26, 2017, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21984&LangID=E.

[30] Tristan Clavel, “540 Children were Murdered Last Year in El Salvador: Report,” InSight Crime, last modified January 31, 2017, accessed October 26, 2017, http://www.insightcrime.org/news-briefs/540-children-murdered-last-year-el-salvador-report.

[31] Casa Alianza, Informe Mensual de la Situación de los Derechos de las Niñas, Niños y Jóvenes en Honduras, July 2017, accessed October 26, 2017, http://www.casa-alianza.org.hn/images/documentos/CAH.2017/1.Inf.Mensuales/7.%20informe%20mensual%20julio%202017%20.pdf.

[32] Interview with NGO Staff, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 31, 2017.

[33] Consejo Noruego para Refugiados, ¿Esconderse o Huir? La Situación Humanitaria y la Educación en Honduras (n.p., 2016), 9.

[34] Mesa de Sociedad Civil contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en el Salvador, Desplazamiento Interno por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en El Salvador, 37-38, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5784803ebe6594ad5e34ea63/t/5880c66b2994ca6b1b94bb77/1484834488111/Desplazamiento+interno+por+violencia+-+Informe+2016.pdf.

[35] Consejo Noruego para Refugiados, ¿Esconderse o Huir? La Situación Humanitaria y la Educación en Honduras (n.p., 2016), 19.

[36] Kids in Need of Defense, Neither Security nor Justice: Sexual and Gender-based Violence and Gang Violence in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, 5, May 4, 2017, accessed October 30, 2017, https://supportkind.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Neither-Security-nor-Justice_SGBV-Gang-Report-FINAL.pdf.

[37] Consejo Noruego para Refugiados, ¿Esconderse o Huir? La Situación Humanitaria y la Educación en Honduras (n.p., 2016), 16-19.

[38] Mesa de Sociedad Civil contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en el Salvador, Desplazamiento Interno por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en El Salvador, 39 and 46, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5784803ebe6594ad5e34ea63/t/5880c66b2994ca6b1b94bb77/1484834488111/Desplazamiento+interno+por+violencia+-+Informe+2016.pdf.

[39] Mesa de Sociedad Civil contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en el Salvador, Desplazamiento Interno por Violencia y Crimen Organizado en El Salvador, 43-44, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5784803ebe6594ad5e34ea63/t/5880c66b2994ca6b1b94bb77/1484834488111/Desplazamiento+interno+por+violencia+-+Informe+2016.pdf.

[40] Interview with NGO staff, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 31, 2017.

[41] Radio Progreso, “Crean Unidad de Atención a Víctimas de Desplazamiento Forzado en Honduras,” Radio Progreso La Voz que Esta con Vos, last modified August 26, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, http://radioprogresohn.net/index.php/comunicaciones/noticias/item/3142-crean-unidad-de-atenci%C3%B3n-a-v%C3%ADctimas-de-desplazamiento-forzado-en-honduras.

[42] Norwegian Refugee Council, Reporte Honduras Desplazamiento (n.p., 2017), 5.

[43] Interview w NGO staff, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 31, 2017.

[44] Interview with official from Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos de El Salvador, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 28, 2017.

[45] Bryan Avelar, ““En Algunos Casos de Desplazamiento la Gente Quiere Cambiarse de Casa… Aprovecharse”” [‘In Some Cases of Displacement People Want to Switch Homes … Gain Advantage”], FACTum, March 22, 2017, accessed October 26, 2017, http://revistafactum.com/en-algunos-casos-de-desplazamiento-la-gente-quiere-cambiarse-de-casa-aprovecharse/.

[46] Salvador Meléndez, “Los Desplazados Invisibles” [The Invisible Displaced], FACTum, December 5, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, http://revistafactum.com/los-desplazados-invisibles/; Carla Ascencio, Victor Peña, and Fred Ramos, “Caluco: El Miedo Queda” [Caluco: The Fear Remains], El Faro, last modified December 11, 2016, accessed October 26, 2017, https://elfaro.net/es/201612/ef_tv/19657/Caluco-el-miedo-queda.htm.

[47] Cristosal, “‘The situation is critical”: displaced family’s lawyer,” Cristosal, last modified October 11, 2017, accessed October 30, 2017, http://www.cristosal.org/news/2017/10/11/the-situation-is-critical-displaced-familys-lawyer.

Jessica Ávalos, ““La situación es crítica”: abogado de familia desplazada” [“The situation is critical”: displaced family’s lawyer], La Prensa Gráfica, October 11, 2017, [Page #], accessed October 30, 2017, https://www.laprensagrafica.com/elsalvador/La-situacion-es-critica-abogado-de-familia-desplazada-20171010-0084.html.

[48] Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, “IACHR and UN Special Rapporteur on Internally Displaced Persons Welcome Decisions in El Salvador,” news release, October 27, 2017, accessed October 30, 2017, http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/media_center/PReleases/2017/170.asp.