Author: Lisa Haugaard

Editor’s Note: This is the seventh part of a series by Latin America Working Group Education Fund on the intersection of human rights, migration, corruption, and public security in Honduras and El Salvador. You can find the full series here.

Peace Brigades International – USA contributed substantially to this report.

Kimberly Dayana Fonseca , a 19-year-old Technical Institute student, was staying at a friend’s house when she heard gunfire coming from the streets where a protest was being held. It was December 4, the first night of the government-imposed curfew. Concerned that her brother was at the protest, and aiming to bring him home, Kimberly went into the street to find him. As she stood at the edge of the crowd, looking for her brother, she was shot in the head by the Military Police. Although protesters tried to administer CPR, she died almost instantly.

In the aftermath of the highly contested November 2017 Honduran presidential elections, massive protests—over 1,000 in total—against suspected electoral fraud and the disputed reelection of President Juan Orlando Hernández took place all over the country. Twenty-two people, most of them protesters, were killed by Honduras’s security forces—all but one by the Military Police. Protests continue in January 2018—and so does the repression. This report details acts of government repression of protesters, journalists, and human rights defenders in the wake of the election. It also suggests the challenges that Honduran citizens, and the international community, face in order to protect human rights at this critical moment.

More than Thirty People Killed, Most of Them Protesters

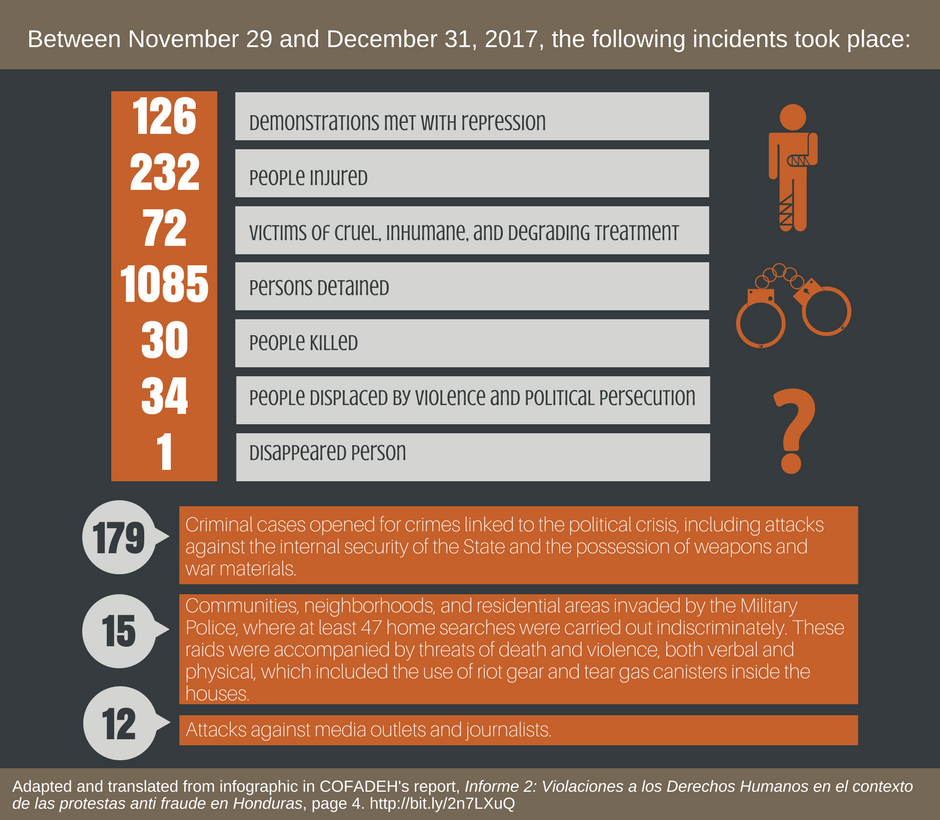

The Honduran government has sent its security forces to quell protests using tear gas, batons, and live ammunition. Thirty people were killed, 232 people were wounded, 1,085 people were detained, and one person was disappeared between November 29 and December 31, 2017, according to the Honduran human rights organization COFADEH. Governmental human rights ombudsman’s office CONADEH documents 31 people killed in post-election violence as of mid-January 2018. More recent deaths—the shooting, apparently by security forces, of Anselmo Villareal in Saba, Colon on January 20, for example—brings the total number of those killed still higher.

repression. Human rights experts from the United Nations and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in a joint statement December 20 statement expressed concern about the excessive use of force. Security forces threw tear gas into crowds, homes, and shopping areas, affecting children and senior citizens, and wounding protesters with gas canisters; they shot into crowds with live ammunition, resulting in protesters and in some cases bystanders being wounded and killed. Security forces prevented wounded protesters from being taken to hospitals, according to COFADEH, and entered hospitals in search of protest leaders.Most of the 30 people killed were protesters. The majority were young men; the victims include three minors. Three of those killed were police, two while enforcing the curfew and one in the context of a demonstration, according to COFADEH. In some cases, protesters threw rocks at police. Acts of looting and vandalism took place, especially in the first few days after the elections.In addition to people killed during demonstrations, there appear to be selective assassinations of protest leaders and Libre party activists. Arnold Fernando Serrano Moncada, who had participated in opposition marches, was found dead after reporting threats, according to COFADEH. The body of activist Seth Jonathan Araujo Andino was found the day after he had participated in a December 4 demonstration in Tegucigalpa. His body bore marks of torture. Twenty-two-year-old Manuel de Jesus Bautista Salvador was forcibly disappeared. Arrested by Military Police near the site of a protest on December 3, he was never seen again. A protest leader in San Juan Pueblo, Wilmer Paredes, was assassinated on January 1, 2018, in a drive-by shooting. On December 16, he had been one of several people subjected to electric shock and degrading treatment by security force members.Of the 30 people killed, 21 people were allegedly killed by the Military Police of Public Order (PMOP), one by the National Preventive Police, 5 by unknown perpetrators, and 2 by private individuals, according to COFADEH.In Geneva, on January 19, the spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights called on the Honduran government to undertake an assessment of the rules of engagement and to avoid using the Military Police and the armed forces in policing demonstrations.

Role of the Military Police

The leading role of the Military Police in these acts of violence against protesters is documented by multiple observers including Amnesty International and in a joint communique, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Honduras and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Military Police are a controversial force of some 5,000 troops under the control of the presidency. They are composed of soldiers who, after receiving a couple of months of training, are deployed to patrol neighborhoods as police. As leader of the Congress in 2013, now-President Juan Orlando Hernández led efforts to pass the legislation that created the Military Police; he subsequently championed a failed effort to make the Military Police permanent in the Constitution. Honduran human rights organizations have been calling for their dismantlement since they were first stood up, warning that soldiers did not have the correct training for police work and that they were a personal force tied to the presidency. Investigating and prosecuting the Military Police for abuses is complicated by legal restrictions preventing the Public Ministry from investigating the Military Police directly. Rather, Military Police are investigated only by special prosecutors who are attached to their military units.During the protests, in contrast to the actions of the Military Police, some members of the police and the COBRA special forces temporarily refused to take actions to repress their fellow citizens.The United States does not provide training and funding directly to the Military Police, largely due to concerns expressed by members of the U.S. Congress. However, some Military Police members likely received U.S. training as soldiers before they were assigned to the Military Police, and Military Police can operate in conjunction with U.S.-funded units. The State Department, responding to human rights conditions attached to aid to the Northern Triangle countries, has requested a plan from the Honduran government to phase out the Military Police and strengthen the Preventive Police. However, this plan has not been made public and its timeline for dissolving the Military Police is sometime in the future. Indeed, the Honduran government has showed no signs of phasing out the Military Police, deploying two new battalions in July 2017.

Failure of the Honduran State to Protect Its Citizens

No state institution acted effectively to protect Honduran citizens from the repressive actions of the Military Police and other security forces. The government’s human rights ombudsman’s office CONADEH did report on the killings in a generic fashion, called on authorities to avoid the use of lethal arms against demonstrators, and prodded the Public Ministry to investigate cases of abuses, but its voice was muted and its actions proved ineffectual. It is not yet clear whether the Public Ministry is investigating the killing and wounding of protesters, but it has been active in filing charges against protesters themselves, according to COFADEH. In 2017, the Honduran legislature passed two laws with a vague definition of terrorism that could result in lengthy jail terms for those involved in protests that block roads or journalists who cover unruly protests—while lessening penalties for corruption.Rather than admitting security forces used excessive force, Security Minister Julian Pacheco Tinoco claimed that those protesting were drug traffickers and gang members—a pattern of vilifying the protesters that other government officials followed. At a minimum, the Protection Mechanism for human rights defenders and journalists failed to take vigorous action to defend the limited number of beneficiaries it covers and did not take any broader action to address the situation of crisis faced by journalists and human rights defenders.

Torture and Cruel Treatment

At least 232 people were injured from November 29 to December 31, 2017, and 72 suffered torture or cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment, according to COFADEH. Honduran human rights organizations received reports of torture in detention including beatings, use of stress positions, and electroshock.COFADEH’s mid-January report details torture carried out against people detained December 1 at the installations of the army’s 105th Infantry Brigade. Those detained were hung with their hands above their heads for hours, beaten with cables and batons, and kicked in the ribs. The United States provided training in 2016 to members of the 105th Infantry Brigade according to the Foreign Military Training Report. Jonathan Fernando Cardona Rodriguez, a twenty-one year old who was parking his motorcycle in front of his house on December 3, was beaten unconscious by Military Police, according to COFADEH. They prevented his brothers from helping him and threatened them with death if they reported anything.A December 16 protest in Agua Tibia, San Juan Pueblo, Atlántida was brutally repressed by National Police officers, as well as by Military Police, according to COFADEH. After teargassing the protesters and firing live ammunition at them, the police pursued them into their homes, breaking down doors and shattering windows. The police forced 30 people to walk back to the highway where their protest had taken place, beating some of them while they were handcuffed. Then the security forces, using cattle prods, applied electric shock to the protesters’ ears as they made them dismantle the barricades they had erected. Six people had to be hospitalized.In 2018, mistreatment of protesters by the security forces continues. Protesters during the month of January were brutally beaten while demonstrating. On January 12, the Military Police attacked protesters with truncheons in Tegucigalpa. In Choluteca on the same date Military Police attacked and beat protesters . The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights in Honduras on January 13 expressed concern about the violence and the excessive use of force.In a number of neighborhoods around San Pedro Sula, Tegucigalpa, and Choluteca, members of the Military Police are reported to have gone door to door at night searching houses without warrants for protest leaders.

Attacks on Journalists

At least a dozen journalists including from Honduran media Marte TV, Prensa Libre de Choluteca, Tribuna TV, and Canal 11, and international media such as The Guardian, were harassed and attacked by security forces, often as they covered protests. For example, on January 12, 2018, two journalists from UNE TV were beaten by 30 members of the army, as the journalists were covering a demonstration, according to the press freedom group C-Libre.Three freelancers from the United States and Britain were detained in the airport and deported. The Jesuit-associated Radio Progreso’s transmission tower was dismantled on December 6 and on December 10, UNE TV denounced that its fiber optics cable was burned, just as the Opposition Alliance called for a demonstration in Tegucigalpa. Social communicator Neptali Rubi of Telesur Canal 33 was detained on December 15 as he covered a demonstration in San Lorenzo.

Attacks and Threats against Human Rights Defenders

Communities, organizations, and individuals defending human rights have been attacked repeatedly in recent weeks. Peace Brigades International’s Honduras team has documented 35 attacks on defenders since November 27. On November 30, for example, Kevhin Ramos, of the Association for Democracy and Human Rights, and Henry Rodriguez, of the Association for Citizen Participation (ACI-Participa), were observing a demonstration led by the Libre Party in the Plaza Cuba, when Kevhin was threatened by General Héctor Iván Mejía and other police officers who surrounded him and pushed him. They threatened him that they were “going to send him to sleep forever.” The day before, both of the human rights defenders had been beaten and insulted by members of the Military Police and special police forces known as the Cobras and the Tigres.The Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH) has been repeatedly targeted. On December 18, while community members were peacefully protesting and playing drums and maracas to ask for strength from their ancestors, police forces composed of Tigres, Cobras, Military Police and special riot police arrived mid-morning and began throwing teargas canisters at demonstrators, in spite of the presence of children and elderly people. Then police forces entered the community itself and threw teargas into a number of houses. That same day, in the evening, unknown assailants fired five shots at community leader Luis Enrique Garcia as he was driving home. He was hit and injured by a bullet. Community members suspect that the attack is linked to their participation in the December 18 road takeover protest, since following that event the community had been under army surveillance. In January, OFRANEH reports, hitmen have made nighttime incursions into the Garifuna communities and reportedly have a list of people to be eliminated.The Broad Movement for Dignity and Justice (MADJ), which is involved in legal support work, has received reports of illegal arrests and raids and has presented writs of habeas corpus on behalf of detained and disappeared individuals. The organization has also taken testimonies about the psychological and emotional damage that the deployment of nearly war-time operations has caused in many communities. On December 8, members of the Military Police and the Cobras raided the Broad Movement’s training facility in San Juan Pueblo, Atlántida, looking, they said, for the general coordinator, attorney Martin Fernandez. The attorney has had precautionary measures from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights since 2013, as have other MADJ leaders in the area. On December 16, members of MADJ participating in the takeover of Highway CA13 in Agua Tibia were brutally attacked by members of the National Police, Military Police, army, and Cobras. Diego Daniel Aguilar, in spite of identifying himself as a human rights defender, was beaten by more than 10 agents. He was among the 30 required to return to the highway and dismantle the barricade as they had their ears shocked with cattle prods.The MADJ has reported that security forces are searching for, harassing, and arresting social leaders as a means of dissuading citizen protest. Security forces are reportedly using unmarked cars, sometimes without license plates, and are making arrests without warrants, as well as harassing people in their houses. At least 47 illegal raids of homes have taken place.Two MADJ members were killed on January 22: sixty-five-year-old Ramón Fiallos in Arizona, Tela and Geovanny Díaz in Pajuiles, Tela. The former was shot by state security forces during a protest. The latter was found shot to death a few hours after men in police uniforms dragged him out of his house in the early morning hours.In a January 19 communique, the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights in Honduras and the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights cited a growing number of reports of intimidation and threats against human rights defenders, as well as members of the media.

U.S. Government Reaction to Post-Electoral Human Rights Abuses

As these human rights abuses and violations of freedom of expression mounted, the U.S. Embassy was mute on the subject. Chargé d’Affaires Heide Fulton, whose twitter account was a main means of public communication by the U.S. Embassy, issued not a single tweet mentioning excessive use of force by Honduran security forces nor calling on the Honduran security forces to exercise restraint, until December 22 when a tweet linked to a State Department statement that, “The government must ensure Honduran security services respect the rights of peaceful protestors, including by ensuring accountability for any violations of those rights.” On January 19, 2018, a tweet recognizing the appointment of a new human rights minister did link to a statement calling for accountability for human rights abuses following the elections and noted that, “Members of the security forces must use force only in accordance with international standards.”Indeed, the State Department appeared to give a seal of approval to the repression when it certified on Tuesday, November 28, two days after the contested elections, that Honduras met the human rights conditions in law, which include to “protect the right of political opposition parties, journalists, trade unionists, human rights defenders, and other civil society activists to operate without interference,” among other matters. While this decision had been in the works for weeks, the Honduran government and National Party cited it as proof of U.S. support for its actions and members of Honduran civil society viewed it as a disheartening sign that the U.S. government was giving President Juan Orlando Hernández a green light to continue the repression.

Recommendations for U.S. Policy Specifically Related to the Post-Electoral Human Rights Crisis

The State Deparment should insist that:

• The Honduran government cease any use of excessive force on protesters and cease harassment of and unwarranted investigations of protest leaders, journalists and social communicators, and human rights defenders;

• The Honduran government immediately act to disband the Military Police;

• The Honduran justice system effectively investigate and prosecute state agents implicated in extrajudicial executions, forced disappearance, and other grave human rights abuses during the post-election period, as well as investigating and prosecuting the material and intellectual authors of the murder of human rights defender Berta Cáceres.

Congress should:

• Press the State Department to take diplomatic action to ensure the Honduran government takes the steps listed above;

• The Foreign Relations Committees and State, Foreign Operations subcommittees should withhold U.S. assistance to the central government of Honduras that is tied to the conditions in law until the Honduran government takes the actions listed above;

• The Armed Services and Defense Appropriations members should also hold up the security assistance administered via the Defense Department and express their serious concerns to the Defense Department and Southern Command.