Authors: Daniella Burgi-Palomino, Emma Buckhout

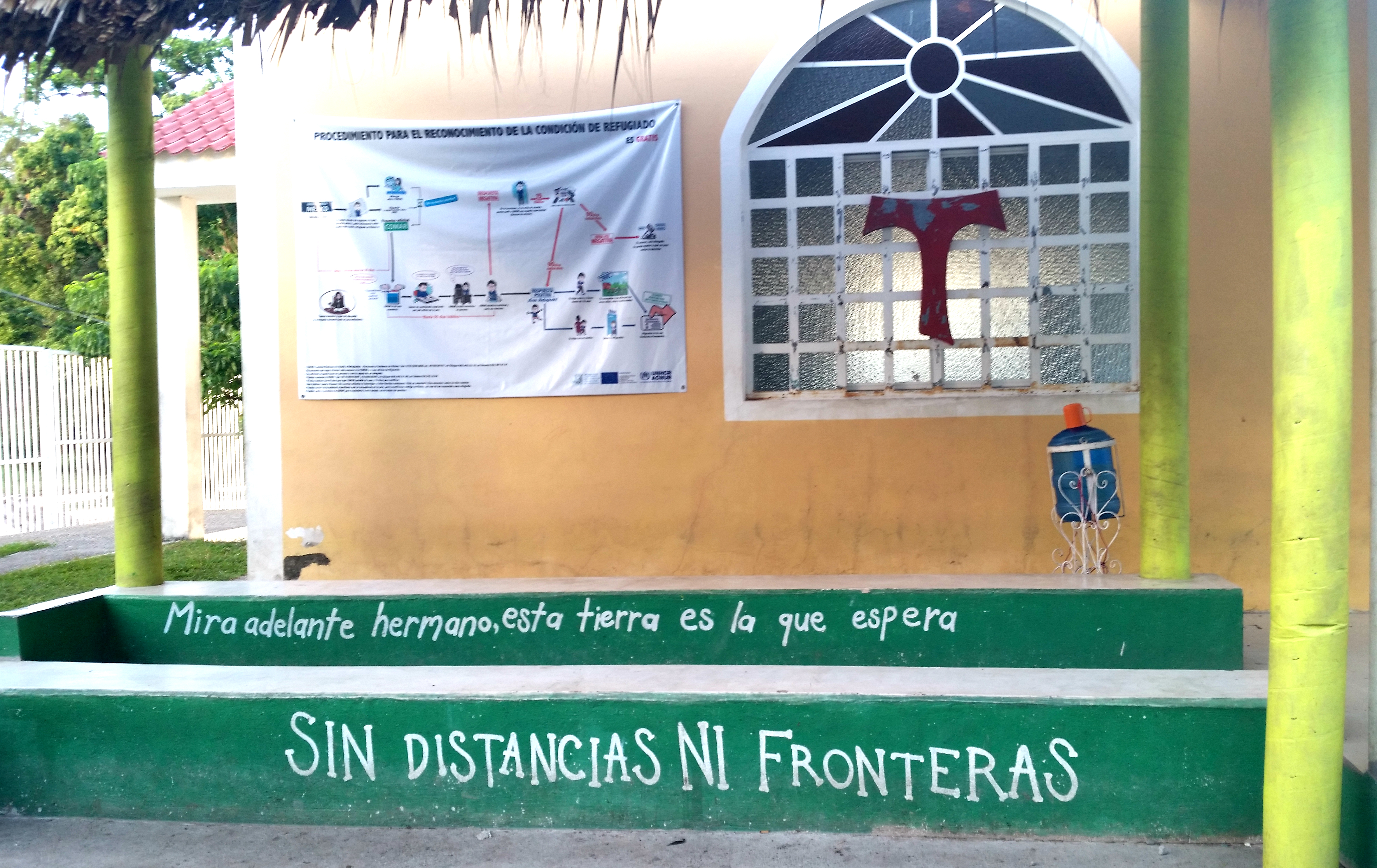

Steps inside La 72 Hogar-Refugio para Migrantes in Tenosique, Mexico. Photo by Daniella Burgi-Palomino |

We traveled to Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala in July 2016 to get a first-hand look at the impact of Mexico’s increased migra-tion enforcement. As Central American migrants and asylum seekers continue to flee, to what degree do families and children have access to seek and receive protection in Mexico? Accompanied by partners on the ground, we met with Mexican asylum and migration authori-ties, staff at migrant shelters, NGOs, researchers, a Central American consul, field representatives of the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and individuals and families seeking asylum.

Two years after the implementation of Plan Frontera Sur (or Southern Border Plan) in Mexico, harsh migration enforcement tactics violate the rights of not only migrants but also Mexican border communities. While individuals and families from Central America now have more information about the possibility of accessing protection in Mexico, the process is difficult and frustrating. Mexico’s asylum system remains not only weak, but structured to discourage children, individuals, and families from seeking protection in the first place. This system contrasts with the growing need to strengthen protection mechanisms as the majority of those arriving in Mexico and the United States have documented fears of returning to their country.

The following are snapshots of the locations we visited and the compelling people to whom we spoke. (Note: names have been changed for protection.)

Tenosique

La 72 Hogar-Refugio para Personas Migrantes is the only migrant shelter in the small city of Tenosique in Mexico’s state of Ta-basco. Located about 25 miles from the Guatemala border, it is an hour drive by car or nearly a two-day walk through remote stretches of thick vegetation, sugar cane fields, and small towns. The shelter’s name commemorates the 2010 massacre of 72 migrants in San Fernando Tamaulipas. The adjacent Guatemalan territory is a remote jungle, so Tenosique has not tradition-ally been a popular crossing point for migrants from Central America. However, there has been a huge spike in the number of migrants arriving, primarily from Honduras, in recent years. La 72 regularly houses 200 people or more each night. While the majority of those arriving are young men, La 72 staff reported alarming increases in the number of women, families, and children since the end of 2015. The shelter has had to increase its space for women and youth, as well as for LGBTI populations. During our two-day visit, there were three young babies and a young pregnant woman, as well as many families and groups from Garifuna (or Afro-Honduran) communities.

Marco’s Story

Marco, a twenty-one-year-old young man from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, had just arrived four days ago at La 72 shelter. As he sat alone in a corner of the patio, the blank and tired expression on his face made him look older. This was his second time crossing into Mexico. Several years ago, the maras (gangs) that controlled his urban neighborhood killed his older brother. The house next to theirs was used by the maras to kill people. When the stress of living amidst such violence became too much, Marcos and his mother fled. They made it to Mexico City but were caught and deported back to Honduras. He decided to take the trip alone this time, but he was worried about the family he had left behind.

When asked if he was going to apply for asylum in Mexico, he looked surprised, but just said, “Sure, lo que Dios quiera (God will-ing).” He said he would attend the next information session held by Asylum Access at the shelter on the process but wondered aloud, “Does my story matter for that [getting asylum]?”

Tapachula

Tapachula, located near the western coast of the Mexico-Guatemala border, in the state of Chiapas is a much more established crossing point than Tenosique. Migrants continue to cross the River Suchiate dividing Guatemala and Mexico quite freely, but now face an increase in checkpoints and raids between the border and Tapachula, and a greater risk of being apprehended, sent to Mexico’s Siglo XXI detention center, and deported. There are several shelters, as well as the Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías de Córdova, which has worked to defend human rights and provide assistance to migrants, asylum seekers, and border communities for eighteen years. Yet, advocates face a frustrating landscape of government bureaucracy and limited access to protection for the individuals and families they are able to assist.

Emma Buckhout with NGO partners by the Suchiate River on the Mexico-Guatemala border. Photo by Daniella Burgi-Palomino. |

Victoria’s Story

Victoria, her husband, and two teenage daughters were denied asylum in Tapachula after fleeing El Salvador. They were appealing their case with the help of Fray Matías staff.

“We fled because they [gangs] were bothering my two girls. At first we tried to move from one block to another in our neighborhood, staying with friends and relatives, but soon it got to be too much. If we would have waited one more day, they would have buried us. There are 16 to 25 murders a day in our municipality and those nearby. We decided to come to Mexico, but we couldn’t leave our room because there were people watching us—people who knew where we were coming from.

“When I went to the asylum interview with COMAR (Mexican Commis-sion to Assist Refugees), the official spent a long time drilling me on my upbringing, my background, where I lived in El Salvador, and only asked me at the end, when there was no time left, why I was scared and why we fled. It felt like they were trying to confuse me about my own information. I was so upset when they told me that my family wouldn’t qualify for asylum that I just walked out—I didn’t even sign the paper. We don’t know what to do now, we’re still scared. We can’t go back, they’ll kill us.”

So What Should Mexico Do?

As seen in the above stories, families and individuals fleeing the Northern Triangle countries of Central America will not be deterred by an increase in border enforcement. Financial and technical support from the United States to Mexico for increased border enforcement along Mexico’s southern border is ineffective, costly, and will not stop those fleeing for their lives. In fact, this strategy has only placed them in more danger. The United States should stop placing pressure on the Mexican government to escalate deportations and instead urge the Mexican government to respond to the protection needs of all Central American asylum seekers within its borders, in particular vulnerable populations such as children, youth, women, and victims of crimes and trafficking. The Mexican government should take a comprehensive approach to strengthening its national asylum system together with international organizations and the civil society organizations that accompanied us on this trip.

And our own country should do the same: recognize Central Americans who are fleeing for their lives as refugees, and not send them back to certain danger.

Daniella Burgi-Palomino is LAWG’s Mexico, Border, and Migration Senior Associate. Emma Buckhout is LAWG’s Mexico, Border, and Migration Program Associate.