Author: Daniella Burgi-Palomino

In November 2016, I joined Mexican and Guatemalan members of the Mesa Transfronteriza de Migraciones y Género and twenty-four representatives from various organizations from across Latin America, Spain, the United States, and Canada on a week-long International Human Rights Observation Mission (Misión de Observación de Derechos Humanos, or MODH by its Spanish acronym) to the Mexico-Guatemala border region. The goal of the MODH was to highlight the range of human rights violations committed against communities and migrants in this region, identify the structural causes and actors behind them, and lift up the work of local organizations in responding to challenges.

To accomplish this goal, we took two different routes that covered a total distance of over 1,300 miles—starting in Guatemala City, traveling through Guatemala’s northern Peten and Quetzeltenango departments and Mexico’s southernmost Chiapas and Tabasco states, to end in the city of San Cristobal de las Casas, Mexico. On the route that I was on, we stopped in more than thirteen communities—some in the rural highlands of Guatemala, others directly along the Mexico-Guatemala border or just a few miles from the official border checkpoints, and others near the Pacific coast—covering vastly different geographies.

Despite the differences in terrain that we covered, we found many similarities in the nature of the human rights abuses that communities and migrants suffered on either side of the border. We heard over and over again from community members that they lived “en resistencia,” or in resistance, to the violent tactics exerted by law enforcement and migration agencies, private security guards, national and multi-national companies, and organized crime.

The cases we documented as members of the Observation Mission not only highlight the work of local communities and migrants themselves as actors of resistance but also the negative impacts of U.S. policies enacted to respond to the 2014 migration surge from Central America.

Protecting Lands in the Face of Persecution in Guatemala

In Xela, Quetzaltenango, one of the largest cities in the highlands of Guatemala with a long history of outward migration, indigenous leaders referred to various infrastructure projects that were being proposed in four municipalities supposedly as a part of the U.S.-backed Alliance for Prosperity Plan. The Plan was announced in November 2014 as a partnership between the United States and the three Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to create economic opportunities and conditions for families and children to remain in their home countries instead of migrating to the United States; however in the communities we visited, the implementation of infrastructure projects appeared to be doing the exact opposite and forcing people out.

In Quetzeltenango and Huehetenango, indigenous leaders told us how the projects were often proposed without prior consultations with communities. In some cases, the projects didn’t respond to community-identified needs and the leaders viewed them as the government’s way of granting more licenses to companies to build additional infrastructure projects in the region-permission to exploit more natural resources at the cost of the indigenous communities. “There didn’t use to be poverty in our communities, they’ve used our resources to make us poor,” one community leader told us. We heard testimonies of the negative impacts of these projects on the quality of water, affecting communities’ long-term health.

|

|

| MODH meets with community leaders in Huehetenango, Guatemala. Photo: Mesa Transfronteriza |

Fighting for their land in the face of increasing aggression and persecution takes a toll on individuals. Some were jailed for their actions to speak out or persecuted. Many shared with us how they had been forced to leave because their land was destroyed by the projects or because they received threats, pressuring them to sell their property to make way for these projects. “These projects are not for the prosperity of the people, that is not true at all,” another leader told us.

We heard about mining projects in Huehetenango that were often implemented alongside the presence of armed actors, including police and military as well as private security guards and paramilitary-type forces sent supposedly to protect communities but that in the end committed violations against them, guarding only business and state interests. The violence had a specific effect on women—“sobre el cuerpo de las mujeres pasa todo” (everything happens over women’s’ bodies), one female community leader told us, drawing a comparison between Mother Earth and women’s’ bodies being destroyed time and time again by various actors since the time of the armed conflict.

Sadly, these cases do not represent isolated realities. They are all too common across Guatemala and throughout the rest of Central America. In a 2016 report by the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders, Guatemala and Honduras were named among the top ten most dangerous countries for environmental human rights defenders in the world.

Continuous Enforcement, Limited Access to Protections in Mexico

Besides being the site of these land struggles by indigenous communities, the northernmost Guatemalan departments also represent the area that Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and less frequently, Honduran migrants cross to enter Mexico. In the current context, many do so fleeing the dire situation in their home countries and with serious protection needs.

Before reaching Mexico, migrants face the possibility of being robbed by Guatemalan national police who often force Salvadorans and Hondurans off buses to extort them. We heard of migrants taking buses from the cities and towns in the middle of the night to avoid this risk.

Once closer to the actual Mexico-Guatemala border, the ports of entry that we visited at Ciudad Cuauhtémoc and Ciudad Hidalgo were similar in that they were relatively porous or had non-stringent enforcement at official border checkpoints. However, increased enforcement along the interior highways and roads began a short distance away from the border. This is a result of Mexico’s stepped-up border enforcement, implemented as a part of its Southern Border Plan in 2014 in conjunction with U.S. pressure to curb migration flows from Central America. This increase in interior enforcement has forced migrants into dangerous and isolated terrain, away from shelters.

|

|

|

|

Ciudad Cuahtemoc, Mexico-Guatemala Border, |

Suchiate River, Mexico-Guatemala border, |

We witnessed examples of the change in migrant routes due to this plan—the Bestia train stop in the town of Arriaga, for example, once frequently sought out by migrants as the closest point of departure from Tapachula, was completely empty when we arrived. We were told that it was because migrants knew they would get apprehended and robbed in a location near the train and now took it at a subsequent stop.

|

|

| La Bestia train stop, Arriaga, Mexico. Photo: Daniella Burgi-Palomino |

We passed multiple “volantas,” or mobile checkpoints, from Ciudad Hidalgo to Tapachula and along the coastal highway from Tapachula towards Tonalá. We also passed one of the joint multi-agency facilities that houses Mexican military, police, customs, and migration agencies, called “CAITFs” (Centros de Atención Integral al Tránsito Fronterizo) located along these highways. Not only was the one we passed close to the border and migrant routes, but also near several mining projects that communities in Chiapas have fought against, a seemingly strategic location for the Mexican government to control migration flows and natural resource exploitation.

We observed this enforcement not just along the interior roads and highways but also in urban settings, in smaller cities receiving an increasing number of asylum seekers. Just days before we arrived in the small town of Frontera Comalapa, Mexico’s National Migration Institute (INM), military, federal, and municipal police had been conducting joint patrols and raids in migrant homes in the search for suspects after a Honduran migrant had allegedly committed a crime against a local. The local migrant comedor had also received unwelcoming comments from neighbors due to its work serving migrants.

This xenophobic and aggressive atmosphere was a contrast to some communities that we visited who had been welcoming Central American migrants for over twenty years. The community of Nueva Linda located not too far from the Mesilla border on the Mexican side had received refugees from Guatemala’s armed conflict in the 1980s and continued to provide support to some of the seasonal agricultural workers who come every year from Guatemala to work in the nearby fields, though increasingly with more difficulties due to increased enforcement operations. These operations have also impacted border communities—local organizations have documented several INM apprehensions of indigenous Mexicans in recent years.

For asylum-seeking families and children, we observed limited and mixed access to protections in our stops along Mexico’s southern border. In the migrant shelter in Frontera Comalapa, we met two young Salvadorans who had fled gangs and were in the process of seeking asylum with the support of a shelter lawyer with Mexico’s Commission to Assist Refugees (COMAR). The process to seek asylum from this part of the border isn’t easy—the closest COMAR office is in Tapachula and asylum interviews are conducted over the phone from the local INM office to which migrants must transport themselves. The men spoke of wanting to find jobs in Mexico, perhaps in the north where they had heard there was work. We asked them what plans they had if their asylum wasn’t granted in Mexico. They were silent, simply repeating that they couldn’t return to El Salvador.

|

|

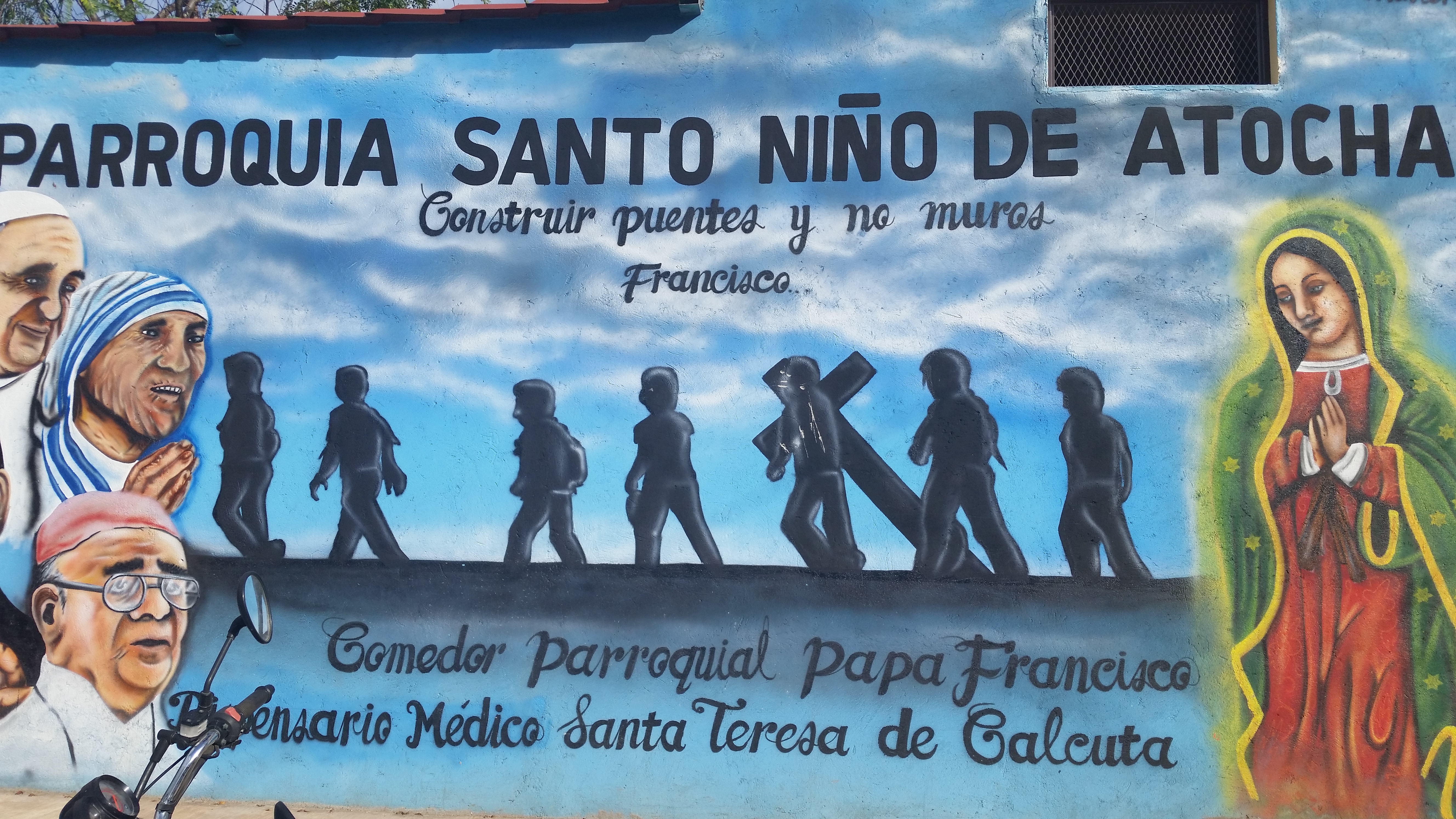

| Mural outside of migrant comedor, Frontera Comalapa, Chiapas, Mexico. Photo: Daniella Burgi-Palomino |

In some of the locations we stopped in, the women were less visible, seeming to be the minority of migrants. Yet our local colleagues shared with us knowledge about a wide network of trafficking rings involving women throughout cities along Mexico’s southern border, alluding to the additional dangers women face along this part of the migrant route.

The dynamics along Mexico’s southern border reflect the challenges Mexico faces as it increasingly becomes a country of destination and not just one of transit. Mexico is set to receive its highest number of asylum seekers from Central America—so far through October 2016 it has already received more than double the amount it received in 2015. Despite this growing need and some improvements in information on how to seek refuge, we observed a Mexican asylum system that remains mostly weak and the continuous existence of a strong enforcement apparatus that prevents many from requesting protection.

Recommendations from Local Communities & Migrants

|

|

| MODH in Fray Matias Office, Tapachula, Mexico. Photo taken by Mesa Transfronteriza |

At the end of the Observation Mission, besides the stories local community activists, indigenous leaders, and migrants shared with me, I remember the demands they asked us to take back to our countries.

In fact, the demands are rights they should already have. The indigenous communities we visited wanted to be able to carry out their own development and not have it be imposed by their governments or companies. They wanted to be consulted prior to the implementation of infrastructure projects, to be able to stay and live in their communities without being persecuted- for the criminalization of land and environmental defenders to cease, for human rights abuses including cases of gender-based violence by law enforcement and private actors to be investigated and sanctioned.

The migrants and asylum seekers I spoke with shared basic rights, too- an opportunity to work and stay in Mexico, to have access to and receive protection there, to not be returned (whether from the United States or Mexico) to a place they fled from in the first place, and a chance for their family and children to live in peace together and make a living.

As it considers how to address migration and development in Mexico and Central America in 2017, these are key recommendations for the United States to consider supporting in future policymaking towards the region. The governments of Mexico and the countries of the Northern Triangle of Central America should also include the participation of communities and migrants in the implementation of policies to respond to the ongoing displacement, militarization and impunity of human rights abuses in the region.

Read the Preliminary Report for the MODH here (currently only available in Spanish).

Longer report to be published and disseminated in early 2017.