Author: Lisa Haugaard

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth part of a series by Latin America Working Group Education Fund on the intersection of human rights, migration, corruption, and public security in Honduras and El Salvador. You can find the full series here.

Many Salvadorans’ lives are affected every day by the brutal impact of gang control of neighborhoods. Young men and women and children are forcibly recruited by gangs. Gangs levy extortion taxes that affect everyone from tortilla sellers to taxi owners and bus drivers to those running companies, stores and restaurants; people are threatened or killed for refusing or being unable to pay. Young women and girls are affected by sexual violence and pressured to become sexual partners with gang members. Youth are killed in gang warfare and by state security forces. Many Salvadorans have to leave their homes due to violence, are internally displaced, and then may have to flee the country, as documented in our blog, “Nowhere to Call Home: Internally Displaced in Honduras and El Salvador.” The violence takes its toll on public security: 44 police and 20 soldiers were killed in 2016. [1] And it takes its toll on young people who see no other alternative but to join the maras.

El Salvador has led the world in homicides per capita in 2015 and 2016, although homicides were reduced from 104 per 100,000 in 2015 to 81 per 100,000 in 2016. It is not yet clear that this drop will be sustainable. Homicides were rising in September and October 2017, and high rates of extortion, robbery, and other crimes continue. [2] The government attributes the recent drop in homicides to its intensified policing efforts and the “extraordinary measures” applied to jailed gang members. But neither the extent of the violence nor welcome reductions in the homicide rate should make us silent about abusive methods among those used to combat gang violence.

A Balanced Plan on Paper, But Mano Dura Prevails

The Mara Salvatrucha 13 and Barrio 18 gangs gained their power over Salvadoran society following deportations of Salvadorans from Los Angeles and other U.S. cities, mainly teenagers and young men whose families had fled the civil war. Years of mano dura (iron fist) strategies by successive Salvadoran governments to fight the gangs have only hardened them, as gang members formed stronger bonds in jail and had little access to rehabilitation programs. “The gangs we have today are the direct consequence of various versions of mano dura,” reflects Florida International University professor José Miguel Cruz. [3] In 2012-13 the first FMLN government of Mauricio Funes tried a different approach, forging a gang truce which for a time resulted in a dramatic drop in homicides. Yet the government’s lack of transparency in implementing the truce, and societal anger about being soft on gangs, among other issues, resulted in a breakdown of the truce. Homicides escalated again following the truce’s collapse.

The current administration led by the FMLN’s Sánchez Cerén developed a balanced plan for addressing terrifying levels of violence: Plan El Salvador Seguro. The plan, drafted by a National Citizen Security and Peaceful Coexistence Council that includes national and municipal government, churches, private sector representatives and violence prevention experts, features prevention and rehabilitation, victims’ services, and generation of employment, as well as law enforcement. The government is rolling out the plan more intensively in targeted municipalities with high levels of violence. This includes ramped up police presence, police sweeps and joint military-police patrols. Then, national and municipal governments are supposed to expand social programs including violence prevention and services for victims. The United States, United Nations Development Programme and other international donors provide important support for these efforts. And there is some success in the first ten targeted municipalities; according to one international donor, as of July 2017, homicide rates were down in all but one.

In practice, however, it is once again the mano dura policies that are most evident. The reaction to the breakdown of the gang truce and the subsequent spike in homicides in 2015 led to a doubling down on hardline strategies. Pressure from the ARENA opposition party and vehement public opinion in favor of the hardline approach given the gangs’ grim chokehold on neighborhoods make it difficult for the Cerén Administration to adhere to a more balanced strategy. Inadequate budget and attention is given to victims, as well as to prevention and rehabilitation. [4] Most concerning of all, extrajudicial executions and other abuses by Salvador’s public security forces, especially the police, are escalating.

Extrajudicial Executions

Extrajudicial executions of suspected gang members by Salvadoran police or army members as well as vigilante squads are a deeply troubling development in El Salvador today.

Online magazines El Faro and Revista Factum have documented supposed shootouts between police and alleged gang members in which all gang members are killed and police emerge unscathed. [5] The Rufina Amaya Human Rights Observatory of the Pasionista Social Service produced the following chart indicating that in 2016, as a result of reported armed confrontations between gangs and police, 96 percent of those killed were alleged gang members while 1 percent were police, 0.3 percent were soldiers, and 3 percent were civilians. [6] The Pasionista Social Service also notes that the great majority of those killed in these supposed shootouts are adolescents or young adults.

Examining reports of those killed during these supposed shootouts, the U.S. State Department noted, “The mortality rate of suspected gang members in confrontations with police during the first six months of the year was 109 percent higher (i.e., more than double) than the 2015 mortality rate, which was itself 41 percent higher than in 2014.” [7] A commissioner of the Inter-American Human Rights Commission, James Cavallaro, notes that he has studied such shootouts in other countries and found that better-equipped and trained police in an armed confrontation can kill two or three times more than their opponents, but not the enormous gap you see in El Salvador. [8]

Revista Factum in August 2017 published an exposé of a group of policemen, claiming to document at least three extrajudicial executions, two sexual abuses of minors, robberies and extortion. The article also revealed a chat room where some 40 police exchanged information about illegal arms sales, torture of gang members and coverups. [9] After the exposé, Revista Factum received numerous threats. And rather than protect the journalists, head of the National Academy of Public Security Jaime Martinez verbally attacked them: “There are journalists who are lending themselves to the gangs’ purposes by presenting themselves as victims.” [10]

It is difficult to get an accurate picture of the extent of these cases. According to the State Department’s 2016 human rights report, “As of October [2016] the attorney general was investigating 53 possible cases of extrajudicial killings. One took place in 2013, none in 2014, 11 in 2015, and 41 in 2016.” [11] The Ombudsman’s office reports 69 cases involving 114 victims of alleged extrajudicial executions between 2014 and 2016, the majority by police. [12]

The Ombudsman’s office has played a vital role in collecting the complaints and working through government channels and via public pronouncements to urge effective investigations and other policies to rein in extrajudicial executions and other abuses. But its mandate limits its ability to stop the abuses.

The Attorney General’s office has launched some investigations. For example, it ordered the arrest of five police officers and five civilians for eight homicides in San Miguel as part of an alleged extermination squad. [13] The Attorney General’s Office also announced the formation of a Special Group Against Impunity, dedicated to investigating this type of crime.

Human rights organizations caution, however, that although there have been some advances in investigating a few cases, the Attorney General’s office has focused primarily on prosecuting the most high-profile cases and those in which bystanders, rather than alleged gang members, have been murdered. And even one of the most high-profile and well-documented cases was not successfully prosecuted.

In July 2016 the Attorney General ordered the arrest of seven police officers on charges related to the supposed shootout at the San Blas farm, documented persistently by El Faro, in which seven alleged gang members were killed as well as one bystander, a worker at the farm. [14] But the Attorney General’s office only prosecuted the murder of the bystander, not of the seven alleged gang members. According to El Faro, the Attorney General’s office failed to present to the judge many of the circumstances surrounding the event, despite the fact that they had been carefully documented by El Faro and the Ombudsman’s office. The judge determined that the bystander, Dennis, was indeed not a gang member, and that he had been the victim of an extrajudicial execution. But because he could not determine which of the police officers fired the shot, all of the police officers were let off, and no one was convicted. [15] Had the Attorney General chosen to prosecute all of the killings, convictions might have been easier to obtain.

In the last couple of years, the U.S. State Department’s human rights bureau and the U.S. Embassy has begun to recognize extrajudicial executions as a serious issue in El Salvador and has urged the Salvadoran government to take steps to address it. The State Department should press vigorously for progress and ensure all U.S. government entities do the same.

Other public security force abuses. Intimidation, cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment, arbitrary detention and violations of due process are some of the most recurrent complaints lodged against the police in the Ombudsman’s office. The Ombudsman’s office also has received reports of instances in which police allow wounded gang members to die rather than transport them to the hospital.

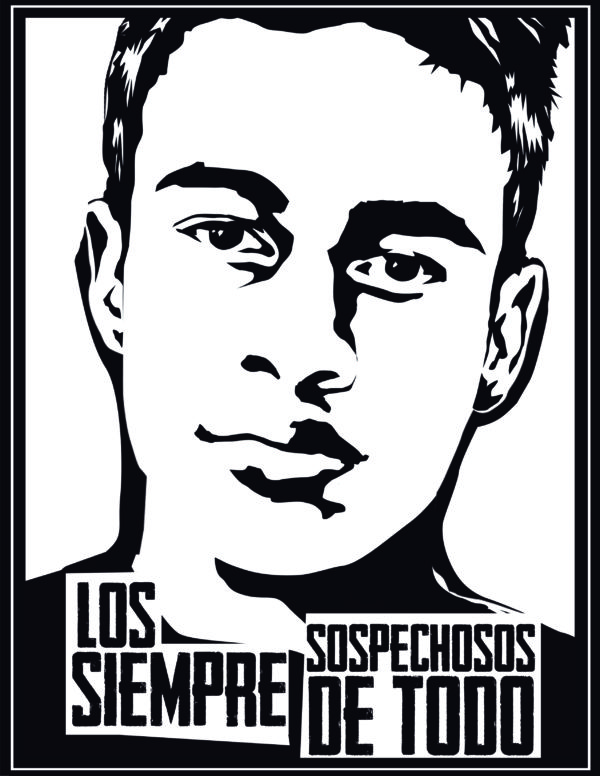

Another disturbing issue is how teenage boys and young men from poor neighborhoods who may be innocent of gang involvement get targeted by police action. One well-documented case is of Daniel Alemán, a 21-year-old who in January 2017 was detained by police while playing soccer and accused of having drugs on his person and drug trafficking. Witnesses who saw him being searched by police deny that he had the drugs on him when arrested. Police also claimed they had picked him up at a different location than the soccer game. The drug trafficking charge was dropped due to the implication that the police planted evidence but Alemán still faced charges of extortion. This is just one example; human rights and humanitarian organizations report that young people routinely are harassed, beaten, and detained without credible evidence of crimes committed.

In addition, the military role in public security is growing in El Salvador, with the number of soldiers involved in joint police-military operations doubling from 5,515 in 2009 to more than 13,000 in 2017. [16] The military are supposed to surround the perimeter while police do the door-to-door operations. Denunciations of abuses by the armed forces are far lower than for the police, but may be on the increase. The Salvadoran government has a plan to withdraw military from policing, but it lacks details and attention to how the police will scale up and improve their operations.

|

|

| Graphic published in Revista Factum |

Official denial of state policy. Salvadoran public security officials vehemently deny that there is a state policy that has promoted these extrajudicial executions and other abuses. “I dismiss and deny, honorable commissioners, I dismiss and deny completely any responsibility of the Salvadoran state in illegal acts that harm fundamental rights or people’s human rights,” asserted Vice Minister of Security Raúl López in front of an Inter-American Commission on Human Rights hearing. [17]

However, extrajudicial executions seem to have escalated so much in a short period of time that it seems likely that state policies have permitted and indeed even encouraged them. These abuses are tolerated and rarely punished. Poor internal controls within the police fail to catch abuses before they escalate. These gross violations of human rights are incentivized at least in an informal way: By societal and media pressure to rein in the gangs at any cost; by high-level government officials who encourage quick and forceful results against the gangs without emphasizing respect for rights; [18] and by failure of police internal controls and judicial authorities to effectively discipline, dismiss, and prosecute many public security member who commit these abuses. It would be important to investigate also whether some implicated in serious abuses have received promotions. Finally, inadequate pay, grueling hours, the enormous strain of the dangerous job they carry out, and lack of psychosocial support for police play a role.

Journalists and human rights groups who report on these abuses also face being labeled as supporters of gangs and terrorism. Some independent media receive extensive death threats for their reporting on organized crime, gang violence, and official abuses. The government fails to protect journalists documenting abuses, including by the simplest measure of speaking out in defense of press freedom when journalists are threatened. [19]

An editorial in Revista Factum offers this no-holds-barred assessment: “To deny it is a vulgar exercise in political opportunism. Or a stupidity. El Salvador is enduring, at least since early 2016, a new war, marked the start by a confrontation between two gangs and between those gangs and the state, and then by a not-officially-recognized policy of the indiscriminate use of public security forces to confront those gangs and whichever person or group they so choose.” [20]

Cracking Down in Prison: Extraordinary Measures

In April 2016, the Salvadoran Congress passed “extraordinary measures” intended to crack down on jailed criminals who were conducting illicit activities from prison. The measures curtail activities by prisoners outside their cells, end visits to prisoners and make prisoners’ court appearances virtual. While the intent was understandable and may have contributed to a drop in homicides, the measures also have had disturbing impacts. According to the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office, the measures were applied broadly to some one-third of the prison population rather than to a select group of problematic prisoners. They have ended access of many prisoners to rehabilitation programs; limited prisoners’ access to lawyers; had an impact on health, resulting in a rise in tuberculosis and mental health issues; and curtailed the access of judges to oversee treatment of prisoners. Forty-seven prisoners died in prison in 2016. Prison rehabilitation programs “were never good, and now they are worse,” according to one government official. [21] Women’s advocates note more positively that the measures have reduced a practice of gangs forcing women to visit jailed members for supposed “conjugal” visits. However, in the long term, jailed gang members completing their sentences will be returning to communities without rehabilitation. [22]

Rehabilitation

While rehabilitation is included in Plan El Salvador Seguro, in practice it has been given short shrift, and the extraordinary measures have limited it further. Rehabilitation programs are difficult to implement, but are an essential component of addressing El Salvador’s violence. A Florida International University study that conducted interviews of 1200 Salvadoran gang members revealed that at some point almost every gang member thought of leaving the gang, but confronted many risks and practical obstacles to starting a new life. Evangelical programs have had some success in rehabilitating gang members, offering a value system and structure to replace the structure of the gangs. [23] Studies suggest the importance of focusing strategies at the community level, not only on individuals. [24]

Rehabilitation of ex-gang members by Salvadoran and well as U.S.-based humanitarian organizations is constrained not only by resources but by legal restrictions. In El Salvador, anti-terrorism legislation scares many organizations away from offering services. U.S. Treasury regulations labeling Salvadoran gangs as terrorist prevent U.S.-based humanitarian agencies from providing these programs. According to one humanitarian worker, “There is such a strong societal push against helping with rehabilitation. You need a wide swath of Salvadoran civil society working on rehabilitation not only because of the scope of the problem but in order to give political backing to the very idea of trying to rehabilitate former gang members.” [25] And these restrictions make it difficult.

Concerning Trends in U.S. Policy

Escalated deportations of Salvadorans from Mexico and the United States are likely to aggravate the country’s problem of gang violence. Sustained help is not provided for young people deported back to El Salvador. According to one humanitarian aid worker, “The reality is returned youth won’t go, even to the existing programs. They are traumatized. They go underground. Services are not offered for people 18 and older, indeed they are seen as criminals. And it is the 16- to 24-year-olds who are most in need of help. So the way they have to get protection is to join a gang.” [26]

The Trump Administration will decide in January 2018 whether to end Temporary Protected Status for almost 200,000 Salvadorans in the United States and it has ended the DACA program, leaving it up to Congress to decide whether the young people known as the “Dreamers” will continue to be able to work and go to university in the United States. And the administration plans to ramp up deportations of the children and teenagers who arrived, many fleeing violence, in recent years. If these measures result in escalating deportations of Salvadorans, reducing the flow of remittances back to families in El Salvador and returning Salvadoran Americans to a situation of high violence and limited opportunity, the difficult public security situation in El Salvador will further deteriorate.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ insistent focus on combating the MS13 gang, which he hammered home in a late July trip to San Salvador, at the site of a brutal crime in Long Island and at many other opportunities, adds another complication to the mix. It provides yet one more pressure on El Salvador’s government to focus mano dura strategies, without balanced attention to rehabilitation and prevention. And this message is delivered without another much needed emphasis: that El Salvador must address the deadly toll of gang violence while respecting human rights.

[1] Observatorio de Derechos Humanos Rufina Amaya, Servicio Social Pasionista, Informe de Violaciones a Derechos Humanos 2016, 14, June 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://sspas.org.sv/informe-casos-violaciones-derechos-humanos-2016/.

[2] Héctor Silva Avalos, “El Salvador Violence Rising Despite Extraordinary Anti-Gang Measures, “ Insight Crime, 3 October 2017, http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/violence-el-salvador-rise-despite-extraordinary-anti-gang-measures.

[3] Roberto Valencia, ““Las pandillas que tenemos hoy son consecuencia directa del ‘manodurismo’”” [“The Gangs We Have Today Are a Direct Consequence of ‘manodurismo'”], El Faro, last modified July 23, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, https://elfaro.net/es/201707/salanegra/20612/%E2%80%9CLas-pandillas-que-tenemos-hoy-son-consecuencia-directa-del-%E2%80%98manodurismo%E2%80%99%E2%80%9D.htm.

[4] According to data from the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, in 2016, only 27.6 percent of the budget for citizen security was channeled to prevention, 3.8 percent to attention to victims, and 68.44 percent to crime-fighting. Data included in Observatorio de Derechos Humanos Rufina Amaya, Informe de Violaciones a Derechos Humanos 2016, 18, June 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://sspas.org.sv/informe-casos-violaciones-derechos-humanos-2016/.

[5] Roberto Valencia, “Daniel, una víctima del ‘manodurismo’ de baja intensidad” [Daniel, a Victim of Low intensity ‘Manodourismo’], El Faro, last modified July 16, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, https://elfaro.net/es/201707/salanegra/20240/Daniel-una-v%C3%ADctima-del-%E2%80%98manodurismo%E2%80%99-de-baja-intensidad.htm;

“La Nueva Guerra” [The New War], Revista Factum, accessed November 9, 2017, http://revistafactum.com/category/nueva-guerra/.

[6] Observatorio de Derechos Humanos Rufina Amaya, Servicio Social Pasionista, Informe de Violaciones a Derechos Humanos 2016, 14, June 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://sspas.org.sv/informe-casos-violaciones-derechos-humanos-2016/.

[7] U.S. Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2016, March 3, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2016&dlid=265586.

[8] Nelsom Rauda Zablah, ““Descarto y niego cualquier responsabilidad del Estado en violaciones a derechos humanos”” [“I dismiss and Deny Any Responsibility of the State in Human Rights Violations”], El Faro, last modified September 6, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, https://elfaro.net/es/201709/el_salvador/20848/%E2%80%9CDescarto-y-niego-cualquier-responsabilidad-del-Estado-en-violaciones-a-derechos-humanos%E2%80%9D.htm;

Anneke Osse and Ignacio Cano, “Police Deadly Use of Firearms: An International Comparison,” The International Journal of Human Rights 21, no. 5 (April 27, 2017), accessed November 9, 2017, doi:10.1080/13642987.2017.1307828

[9] Bryan Avelar and Juan Martinez d’Aubuisson, “En la Intimidad del Escuadrón de la Muerte de la Policia” [In the Privacy of the Police Death Squad], Revista Factum, last modified August 22, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://revistafactum.com/en-la-intimidad-del-escuadron-de-la-muerte-de-la-policia/.

[10] Nelson Rauda Zablah, “Jaime Martínez contradice a Jaime Martínez” [Jaime Martínez Contradicts Jaime Martínez], El Faro, last modified September 14, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, https://elfaro.net/es/201709/el_salvador/20883/Jaime-Mart%C3%ADnez-contradice-a-Jaime-Mart%C3%ADnez.htm.

[11] U.S. Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2016, March 3, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2016&dlid=265586.

[12] Observatorio de Derechos Humanos Rufina Amaya, Servicio Social Pasionista, Informe de Violaciones a Derechos Humanos 2016, 14, June 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://sspas.org.sv/informe-casos-violaciones-derechos-humanos-2016/..

[13] U.S. Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2016, March 3, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2016&dlid=265586.

[14] Roberto Valenia, Oscar Martinez, and Daniel Valencia Caravantes, “La Policía masacró en la finca San Blas” [Police Massacre in San Blas Estate], El Faro, last modified July 22, 2015, accessed November 9, 2017, https://salanegra.elfaro.net/es/201507/cronicas/17205/La-Polic%C3%ADa-masacr%C3%B3-en-la-finca-San-Blas.htm.

[15] Roberto Valencia, “El juicio bufo de San Blas” [The Farcical Trial of San Blas], El Faro, last modified September 22, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, https://elfaro.net/es/201709/salanegra/20868/El-juicio-bufo-de-San-Blas.htm.

[16] 2017 figure: Salvador Ahora, Tves, first broadcast November 3, 2017, hosted by Wendy Monterrosa; 2009 figure: Observatorio de Derechos Humanos Rufina Amaya, Informe de Violaciones a Derechos Humanos 2016, 17, June 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://sspas.org.sv/informe-casos-violaciones-derechos-humanos-2016/.

[17] Nelsom Rauda Zablah, ““Descarto y niego cualquier responsabilidad del Estado en violaciones a derechos humanos”” [“I dismiss and Deny Any Responsibility of the State in Human Rights Violations”], El Faro, last modified September 6, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, https://elfaro.net/es/201709/el_salvador/20848/%E2%80%9CDescarto-y-niego-cualquier-responsabilidad-del-Estado-en-violaciones-a-derechos-humanos%E2%80%9D.htm.

[18] As the head of the National Academy of Public Security, Jaime Martinez, said to a group of police completing a tactical training class, “Do not let your hand tremble. There’s no room to be thinking, that human rights are in the midst of this, that if there is a criticism by the press or international organizations; in the moment in which the state’s legitimacy is disrespected, you need to make use of all tactics and all team training that you have.” “‘Que no les tiemble la mano’”: director de ANSP a policías” [“Do Not Hesitate”: ANSP Director to Police], La Prensa Grafica, last modified May 6, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, https://www.laprensagrafica.com/elsalvador/Que-no-les-tiemble-la-mano-director-de-ANSP-a-policias-20170506-0052.html.

[19] “CIDH ordena investigar amenazas contra periodistas de Revista Factum” [IACHR Orders Investigating Threats Against Journalists of Factum Magazine], Revista Factum, last modified November 3, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://revistafactum.com/cidh-ordena-investigar-amenazas-contra-periodistas-de-revista-factum/.

[20] “La nueva guerra” [The New War], Revista Factum, last modified November 22, 2016, accessed November 9, 2017, http://revistafactum.com/la-nueva-guerra/.

[21] Interview with Salvadoran government official by Lisa Haugaard, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 28, 2017

[22] Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos, Informe preliminar sobre el impacto de las medidas extraordinarias para combatir la delincuencia, en el ámbito de los derechos humanos, 21, June 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://www.pddh.gob.sv/migrantes/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Informe-preliminar-sobre-el-impacto-de-las-medidas-extraordinarias-para-combatir-la-delincuencia-en-el-ambito-de-los-DH-FIRMADO.1.pdf.

[23] Juan Martinez d’Aubuison and Bryan Avelar, “Ya no somos padilleros” [We Are Not Gang Members Anymore], Revista Factum, last modified February 3, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://revistafactum.com/ya-no-somos-pandilleros/.

[24] Sonja Wolf, Mano Dura: The Politics of Gang Control in El Salvador (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2017), 227.

[25] Interview with a humanitarian aid worker by Lisa Haugaard, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 31, 2017.

[26] Interview with a humanitarian aid worker by Lisa Haugaard, San Salvador, El Salvador, July 31, 2017.