Authors: Daniella Burgi-Palomino, Emma Buckhout

One year ago on the nights of September 26and 27, 180 people suffered grave human rights violations at the hands of state law enforcement officials and organized crime in the city of Iguala, in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. According to the recently released report on the preliminary conclusions of the Interdisciplinary Group of International Experts accompanying the case, six people were extrajudicially executed, over 40 were wounded, more than 100 experienced attacks on their lives and 43 students from the Ayotzinapa rural teacher’s school were arrested and forcibly disappeared. A year later the exact details of their disappearance, what they endured, and the motives for the violence used against them remain unclear.

One year ago on the nights of September 26and 27, 180 people suffered grave human rights violations at the hands of state law enforcement officials and organized crime in the city of Iguala, in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. According to the recently released report on the preliminary conclusions of the Interdisciplinary Group of International Experts accompanying the case, six people were extrajudicially executed, over 40 were wounded, more than 100 experienced attacks on their lives and 43 students from the Ayotzinapa rural teacher’s school were arrested and forcibly disappeared. A year later the exact details of their disappearance, what they endured, and the motives for the violence used against them remain unclear.While the disappearance of the 43 students and the government’s failed investigation of the case has been widely reported and received much international attention, on this one-year anniversary we look beyond the emblematic “Ayotzinapa 43” number. We seek to remember the individual disappeared students and magnify and support the efforts of their friends and families, the other victims of this brutal event, who are still seeking justice to this day in the face of enormous challenges. The 43 students were young men, ranging in ages from 17 to 33, mostly self-described campesinos, or peasants, from the towns neighboring the Ayotzinapa school. Their families and relatives described many of them as respectful, studious and humble students who were always seeking to help others. Several of them, like Marcial Pablo Baranda, Mauricio Ortega Valerio and Magdaleno Rubén Lauro Villegas, wanted to use their knowledge of indigenous languages to teach bilingually while others like Bernardo Flores Alcaraz and Benjamín Ascencio Bautista wanted to address illiteracy in the nearby, often neglected communities. Their efforts to study never came easy. Jhosivani Guerrero de la Cruz was used to walking 5 miles per day to attend classes in elementary and middle school.

As their friends have shared, the 43 students were also young men like any of their age with interests in pop culture, music and soccer. Christian Alfonso Rodríguez Telumbre, whose father traveled on a caravan across the U.S. to raise awareness about the case, was an avid folkloric dancer, a passion, his family said, that was only matched by his desire to be a teacher one day. And yet the 43 students had a deep sense of social consciousness; on the night they disappeared they were seeking to travel to Mexico City to attend memorial events for the 1968 Tlatelolco student massacre, as they had in years past.

As the Group of Experts’ report explains, the perpetrators of any forced disappearance aim to eliminate all traces of their actions, spread confusion to victims’ families and keep the facts unknown. The defining element of forced disappearances is that they spread fear and terror and in doing so erase the act, the victim and the role of those responsible. Disappearances have particularly painful impact on the relatives of the missing who are left to fight for answers to a constant and ambiguous loss.

The Mexican government’s management of the investigation of the September 26 and 27 events in Iguala over the past year, in addition to not solving the crime, has failed to provide the deserved attention, respect and protection to the families of the students. Since the beginning of the investigation when the Attorney General’s Office took one week after the incidents to officially take on the case, the families and their suffering have been overlooked time and time again.

A first meeting between the families of the disappeared students and President Enrique Peña Nieto came only 33 days after the incidents, on October 29, 2014. A week later, former Attorney General, Jesús Murillo Karam presented the government’s findings in a press conference that included videos of suspects recounting their alleged attacks against the students in graphic detail and that ended with his now infamous quote “Ya me canse” (“I’m already tired”), indicating that he was already tired of answering questions. By January 27, 2015, four months after the incident, Murillo Karam declared the case officially closed, despite repeated calls by the students’ families and civil society organizations highlighting inefficiencies in the investigation.

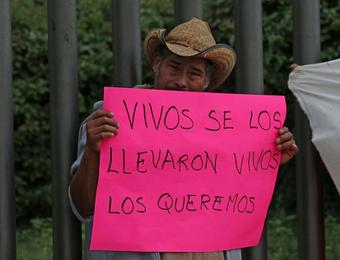

Together with Argentine forensic anthropologists, the Centro de la Montaña Tlachinollan and other organizations that have accompanied the families for the past year, the families found the strength to lead marches on the monthly anniversary of the disappearances, carrying posters with pictures and the names of the 43 disappeared students. Their journey has taken them across the United States, Europe and to United Nations offices in Geneva.

On the seven-month anniversary in April of this year, the families and supporting organizations erected a more than seven-foot-tall, three-piece, red “+43” structure in the midst of Mexico City’s busy Reforma Avenue in a physical and visible remembrance of the students and the search to find them. The plaque on the structure reads “Vivos se los llevaron, vivos los queremos” (“they were taken alive, we want them back alive”), the emblematic call to action used by the social movement to find the students.

Recent actions by Mexican government officials such as their decision to inform family members only minutes before the public announcements of a likely DNA match with disappeared student Jhosivani Guerrero de la Cruz on September 17th, have only continued the pattern of failing to respect family members. During the press conference when Attorney General Arely Gómez made this announcement, Jhosivani’s name was barely mentioned. His remains were instead referred to by the number assigned to them. Yesterday, President Peña Nieto met with the families once again in response to their request following the Group of Experts’ report. The parents characterized the three-hour closed door meeting, at “unfruitful,” and were once again disappointed in the lack of concrete response by the government and the “cold” and “insensitive” treatment they received. While Peña Nieto announced that he will appoint a new special prosecutor for the search of disappeared people nationally, he did not respond to their specific request of a new internationally supervised investigation unit for the Ayotzinapa students’ case.

We commend the Mexican government for supporting the extension of the Group of Experts’ investigation for another six months, and we hope that it will demonstrate real political will to comply with the Group’s recommendations. On the eve of the one-year anniversary of the human rights violations committed in Iguala, along with supporting the Group of Experts’ recommendations thus far and critical ongoing investigation, LAWG remembers the 43 disappeared students and their families. We recognize their bravery in searching for their loved ones throughout the past year and call for protection, respect and reparations to the victims and their families to be a central focus in the next phase of the Ayotzinapa investigation.